TORONTO — A vast electronic spying operation has infiltrated computers and has stolen documents from hundreds of government and private offices around the world, including those of the Dalai Lama, Canadian researchers have concluded.

In a report to be issued this weekend, the researchers said that the system was being controlled from computers based almost exclusively in China, but that they could not say conclusively that the Chinese government was involved.

The researchers, who are based at the Munk Center for International Studies at the University of Toronto, had been asked by the office of the Dalai Lama, the exiled Tibetan leader whom China regularly denounces, to examine its computers for signs of malicious software, or malware.

Their sleuthing opened a window into a broader operation that, in less than two years, has infiltrated at least 1,295 computers in 103 countries, including many belonging to embassies, foreign ministries and other government offices, as well as the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan exile centers in India, Brussels, London and New York.

The researchers, who have a record of detecting computer espionage, said they believed that in addition to the spying on the Dalai Lama, the system, which they called GhostNet, was focused on the governments of South Asian and Southeast Asian countries.

Intelligence analysts say many governments, including those of China, Russia and the United States, and other parties use sophisticated computer programs to covertly gather information.

The newly reported spying operation is by far the largest to come to light in terms of countries affected.

This is also believed to be the first time researchers have been able to expose the workings of a computer system used in an intrusion of this magnitude.

Still going strong, the operation continues to invade and monitor more than a dozen new computers a week, the researchers said in their report, “Tracking ‘GhostNet’: Investigating a Cyber Espionage Network.” They said they had found no evidence that United States government offices had been infiltrated, although a NATO computer was monitored by the spies for half a day and computers of the Indian Embassy in Washington were infiltrated.

The malware is remarkable both for its sweep — in computer jargon, it has not been merely “phishing” for random consumers’ information, but “whaling” for particular important targets — and for its Big Brother-style capacities. It can, for example, turn on the camera and audio-recording functions of an infected computer, enabling monitors to see and hear what goes on in a room. The investigators say they do not know if this facet has been employed.

The researchers were able to monitor the commands given to infected computers and to see the names of documents retrieved by the spies, but in most cases the contents of the stolen files have not been determined. Working with the Tibetans, however, the researchers found that specific correspondence had been stolen and that the intruders had gained control of the electronic mail server computers of the Dalai Lama’s organization.

The electronic spy game has had at least some real-world impact, they said. For example, they said, after an e-mail invitation was sent by the Dalai Lama’s office to a foreign diplomat, the Chinese government made a call to the diplomat discouraging a visit. And a woman working for a group making Internet contacts between Tibetan exiles and Chinese citizens was stopped by Chinese intelligence officers on her way back to Tibet, shown transcripts of her online conversations and warned to stop her political activities.

The Toronto researchers said they had notified international law enforcement agencies of the spying operation, which in their view exposed basic shortcomings in the legal structure of cyberspace. The F.B.I. declined to comment on the operation.

Although the Canadian researchers said that most of the computers behind the spying were in China, they cautioned against concluding that China’s government was involved. The spying could be a nonstate, for-profit operation, for example, or one run by private citizens in China known as “patriotic hackers.”

“We’re a bit more careful about it, knowing the nuance of what happens in the subterranean realms,” said Ronald J. Deibert, a member of the research group and an associate professor of political science at Munk. “This could well be the C.I.A. or the Russians. It’s a murky realm that we’re lifting the lid on.”

A spokesman for the Chinese Consulate in New York dismissed the idea that China was involved. “These are old stories and they are nonsense,” the spokesman, Wenqi Gao, said. “The Chinese government is opposed to and strictly forbids any cybercrime.”

The Toronto researchers, who allowed a reporter for The New York Times to review the spies’ digital tracks, are publishing their findings in Information Warfare Monitor, an online publication associated with the Munk Center.

At the same time, two computer researchers at Cambridge University in Britain who worked on the part of the investigation related to the Tibetans, are releasing an independent report. They do fault China, and they warned that other hackers could adopt the tactics used in the malware operation.

“What Chinese spooks did in 2008, Russian crooks will do in 2010 and even low-budget criminals from less developed countries will follow in due course,” the Cambridge researchers, Shishir Nagaraja and Ross Anderson, wrote in their report, “The Snooping Dragon: Social Malware Surveillance of the Tibetan Movement.”

In any case, it was suspicions of Chinese interference that led to the discovery of the spy operation. Last summer, the office of the Dalai Lama invited two specialists to India to audit computers used by the Dalai Lama’s organization. The specialists, Greg Walton, the editor of Information Warfare Monitor, and Mr. Nagaraja, a network security expert, found that the computers had indeed been infected and that intruders had stolen files from personal computers serving several Tibetan exile groups.

Back in Toronto, Mr. Walton shared data with colleagues at the Munk Center’s computer lab.

One of them was Nart Villeneuve, 34, a graduate student and self-taught “white hat” hacker with dazzling technical skills. Last year, Mr. Villeneuve linked the Chinese version of the Skype communications service to a Chinese government operation that was systematically eavesdropping on users’ instant-messaging sessions.

Early this month, Mr. Villeneuve noticed an odd string of 22 characters embedded in files created by the malicious software and searched for it with Google. It led him to a group of computers on Hainan Island, off China, and to a Web site that would prove to be critically important.

In a puzzling security lapse, the Web page that Mr. Villeneuve found was not protected by a password, while much of the rest of the system uses encryption.

Mr. Villeneuve and his colleagues figured out how the operation worked by commanding it to infect a system in their computer lab in Toronto. On March 12, the spies took their own bait. Mr. Villeneuve watched a brief series of commands flicker on his computer screen as someone — presumably in China — rummaged through the files. Finding nothing of interest, the intruder soon disappeared.

Through trial and error, the researchers learned to use the system’s Chinese-language “dashboard” — a control panel reachable with a standard Web browser — by which one could manipulate the more than 1,200 computers worldwide that had by then been infected.

Infection happens two ways. In one method, a user’s clicking on a document attached to an e-mail message lets the system covertly install software deep in the target operating system. Alternatively, a user clicks on a Web link in an e-mail message and is taken directly to a “poisoned” Web site.

The researchers said they avoided breaking any laws during three weeks of monitoring and extensively experimenting with the system’s unprotected software control panel. They provided, among other information, a log of compromised computers dating to May 22, 2007.

They found that three of the four control servers were in different provinces in China — Hainan, Guangdong and Sichuan — while the fourth was discovered to be at a Web-hosting company based in Southern California.

Beyond that, said Rafal A. Rohozinski, one of the investigators, “attribution is difficult because there is no agreed upon international legal framework for being able to pursue investigations down to their logical conclusion, which is highly local.”

nyt

Sunday, March 29, 2009

Saturday, March 28, 2009

The Texas-Size Debate Over Teaching Evolution

Sure, discuss Darwin's 'strengths and weaknesses.' Just not in biology textbooks.

Christopher Hitchens

NEWSWEEK

From the magazine issue dated Apr 6, 2009

Mention the name "Texas" and the word "schoolbook" to many people of a certain age (such as my own) and the resulting free association will come up with the word "depository" and the image of Lee Harvey Oswald crouching on its sixth floor. In Dallas for the Christian Book Expo recently, I had a view of Dealey Plaza and its most famous building from my hotel room, so the suggestion was never far from my mind.

But last week Texas and schoolbooks meant something else altogether when the state Board of Education, in a muddled decision, rejected a state science curriculum that required teachers to discuss the "strengths and weaknesses" of the theory of evolution. Instead, the board allowed "all sides" of scientific theories to be taught. The vote was watched as something more than a local or bookish curiosity. Just as the Christian Book Expo is one of the largest events on the nation's publishing calendar, so the Lone Star State commands such a big share of the American textbook market that many publishers adapt to the standards that it sets, and sell the resulting books to non-Texans as well.

In many ways, this battle can be seen as the last stand of the Protestant evangelicals with whom I was mingling and debating. It's been a rather dismal time for them lately. In the last election they barely had a candidate after Mike Huckabee dropped out and, some would say, not much of one before that. Many Republicans now see them as more of a liability than an asset. As a proportion of the population they are shrinking, and in ethical terms they find themselves more and more in the wilderness of what some of them morosely called, in conversation with me, a "post-Christian society." Perhaps more than any one thing, the resounding courtroom defeat that they suffered in December 2005 in the conservative district of Dover, Pa., where the "intelligent design" plaintiffs were all but accused of fraud by a Republican judge, has placed them on the defensive. Thus, even if the Texas board had defiantly voted to declare evolution to be questionable and debatable, its decision could still have spelled the end of a movement rather than the revival of one.

Yet I find myself somewhat drawn in by the quixotic idea that we should "teach the argument." I am not a scientist, and all that I knew as an undergraduate about the evolution debate came from the study of two critical confrontations. The first was between Thomas Huxley (Darwin's understudy, ancestor of Aldous and coiner of the term "agnostic") and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce (third son of the great Christian emancipator William) at the Oxford University Museum in 1860. The second was the "Monkey Trial" in Dayton, Tenn., in 1925, which pitted the giant of Protestant fundamentalism, William Jennings Bryan, against Clarence Darrow and H. L. Mencken. Every educated person should know the arguments that were made in these transatlantic venues.

So by all means let's "be honest with the kids," as Dr. Don McLeroy, the chairman of the Texas education board, wants us to be. The problem is that he is urging that the argument be taught, not in a history or in a civics class, but in a biology class. And one of his supporters on the board, Ken Mercer, has said that evolution is disproved by the absence of any transitional forms between dogs and cats. If any state in the American union gave equal time in science class to such claims, it would certainly make itself unique in the world (perhaps no shame in that). But it would also set a precedent for the sharing of the astronomy period with the teaching of astrology, or indeed of equal time as between chemistry and alchemy. Less boring perhaps, but also much less scientific and less educational.

The Texas anti-Darwin stalwarts also might want to beware of what they wish for. The last times that evangelical Protestantism won cultural/ political victories—by banning the sale of alcohol, prohibiting the teaching of evolution and restricting immigration from Catholic countries—the triumphs all turned out to be Pyrrhic. There are some successes that are simply not survivable. If by any combination of luck and coincidence any religious coalition ever did succeed in criminalizing abortion, say, or mandating school prayer, it would swiftly become the victim of a backlash that would make it rue the day. This will apply with redoubled force to any initiative that asks the United States to trade its hard-won scientific preeminence against its private and unofficial pieties. This country is so constituted that no one group, and certainly no one confessional group, is able to dictate its own standards to the others. There are days when I almost wish the fundamentalists could get their own way, just so that they would find out what would happen to them.

Perhaps dimly aware that they don't want a total victory, either, McLeroy and his allies now say that they ask for evolution to be taught only with all its "strengths and weaknesses." But in this, they are surely being somewhat disingenuous. When their faction was strong enough to demand an outright ban on the teaching of what they call "Darwinism," they had such a ban written into law in several states. Since the defeat and discredit of that policy, they have passed through several stages of what I am going to have to call evolution. First, they tried to get "secular humanism" classified as a "religion," so that it would meet the First Amendment's disqualification for being taught with taxpayers' money. (That bright idea was Pat Robertson's.) Then they came up with the formulation of "creation science," picking up on anomalies and gaps in evolution and on differences between scientific Darwinists like Richard Dawkins and Stephen Jay Gould. Next came the ingratiating plea for "equal time"—what could be more American than that?—and now we have the rebranded new coinage of "intelligent design" and the fresh complaint that its brave advocates are, so goes the title of a recent self-pitying documentary, simply "expelled" from the discourse.

It's not just that the overwhelming majority of scientists are now convinced that evolution is inscribed in the fossil record and in the lineaments of molecular biology. It is more that evolutionists will say in advance which evidence, if found, would refute them and force them to reconsider. ("Rabbit fossils in the pre-Cambrian layer" was, I seem to remember, the response of Prof. J.B.S. Haldane.) Try asking an "intelligent design" advocate to stipulate upfront what would constitute refutation of his world view and you will easily see the difference between the scientific method and the pseudoscientific one.

But that is just my opinion. And I certainly do not want it said that my side denies a hearing to the opposing one. In the spirit of compromise, then, I propose the following. First, let the school debating societies restage the wonderful set-piece real-life dramas of Oxford and Dayton, Tenn. Let time also be set aside, in our increasingly multiethnic and multicultural school system, for children to be taught the huge variety of creation stories, from the Hindu to the Muslim to the Australian Aboriginal. This is always interesting (and it can't be, can it, that the Texas board holdouts think that only Genesis ought to be so honored?). Second, we can surely demand that the principle of "strengths and weaknesses" will be applied evenly. If any church in Texas receives a tax exemption, or if any religious institution is the beneficiary of any subvention from the Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, we must be assured that it will devote a portion of its time to laying bare the "strengths and weaknesses" of the religious world view, and also to teaching the works of Voltaire, David Hume, Benedict de Spinoza, Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson. This is America. Let a hundred flowers bloom, and a thousand schools of thought contend. We may one day have cause to be grateful to the Texas Board of Education for lighting a candle that cannot be put out.

Hitchens, a NEWSWEEK contributor, is a columnist for Vanity Fair. His book “God Is Not Great” is newly available in paperback.

http://www.newsweek.com/id/191400/output/print

Christopher Hitchens

NEWSWEEK

From the magazine issue dated Apr 6, 2009

Mention the name "Texas" and the word "schoolbook" to many people of a certain age (such as my own) and the resulting free association will come up with the word "depository" and the image of Lee Harvey Oswald crouching on its sixth floor. In Dallas for the Christian Book Expo recently, I had a view of Dealey Plaza and its most famous building from my hotel room, so the suggestion was never far from my mind.

But last week Texas and schoolbooks meant something else altogether when the state Board of Education, in a muddled decision, rejected a state science curriculum that required teachers to discuss the "strengths and weaknesses" of the theory of evolution. Instead, the board allowed "all sides" of scientific theories to be taught. The vote was watched as something more than a local or bookish curiosity. Just as the Christian Book Expo is one of the largest events on the nation's publishing calendar, so the Lone Star State commands such a big share of the American textbook market that many publishers adapt to the standards that it sets, and sell the resulting books to non-Texans as well.

In many ways, this battle can be seen as the last stand of the Protestant evangelicals with whom I was mingling and debating. It's been a rather dismal time for them lately. In the last election they barely had a candidate after Mike Huckabee dropped out and, some would say, not much of one before that. Many Republicans now see them as more of a liability than an asset. As a proportion of the population they are shrinking, and in ethical terms they find themselves more and more in the wilderness of what some of them morosely called, in conversation with me, a "post-Christian society." Perhaps more than any one thing, the resounding courtroom defeat that they suffered in December 2005 in the conservative district of Dover, Pa., where the "intelligent design" plaintiffs were all but accused of fraud by a Republican judge, has placed them on the defensive. Thus, even if the Texas board had defiantly voted to declare evolution to be questionable and debatable, its decision could still have spelled the end of a movement rather than the revival of one.

Yet I find myself somewhat drawn in by the quixotic idea that we should "teach the argument." I am not a scientist, and all that I knew as an undergraduate about the evolution debate came from the study of two critical confrontations. The first was between Thomas Huxley (Darwin's understudy, ancestor of Aldous and coiner of the term "agnostic") and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce (third son of the great Christian emancipator William) at the Oxford University Museum in 1860. The second was the "Monkey Trial" in Dayton, Tenn., in 1925, which pitted the giant of Protestant fundamentalism, William Jennings Bryan, against Clarence Darrow and H. L. Mencken. Every educated person should know the arguments that were made in these transatlantic venues.

So by all means let's "be honest with the kids," as Dr. Don McLeroy, the chairman of the Texas education board, wants us to be. The problem is that he is urging that the argument be taught, not in a history or in a civics class, but in a biology class. And one of his supporters on the board, Ken Mercer, has said that evolution is disproved by the absence of any transitional forms between dogs and cats. If any state in the American union gave equal time in science class to such claims, it would certainly make itself unique in the world (perhaps no shame in that). But it would also set a precedent for the sharing of the astronomy period with the teaching of astrology, or indeed of equal time as between chemistry and alchemy. Less boring perhaps, but also much less scientific and less educational.

The Texas anti-Darwin stalwarts also might want to beware of what they wish for. The last times that evangelical Protestantism won cultural/ political victories—by banning the sale of alcohol, prohibiting the teaching of evolution and restricting immigration from Catholic countries—the triumphs all turned out to be Pyrrhic. There are some successes that are simply not survivable. If by any combination of luck and coincidence any religious coalition ever did succeed in criminalizing abortion, say, or mandating school prayer, it would swiftly become the victim of a backlash that would make it rue the day. This will apply with redoubled force to any initiative that asks the United States to trade its hard-won scientific preeminence against its private and unofficial pieties. This country is so constituted that no one group, and certainly no one confessional group, is able to dictate its own standards to the others. There are days when I almost wish the fundamentalists could get their own way, just so that they would find out what would happen to them.

Perhaps dimly aware that they don't want a total victory, either, McLeroy and his allies now say that they ask for evolution to be taught only with all its "strengths and weaknesses." But in this, they are surely being somewhat disingenuous. When their faction was strong enough to demand an outright ban on the teaching of what they call "Darwinism," they had such a ban written into law in several states. Since the defeat and discredit of that policy, they have passed through several stages of what I am going to have to call evolution. First, they tried to get "secular humanism" classified as a "religion," so that it would meet the First Amendment's disqualification for being taught with taxpayers' money. (That bright idea was Pat Robertson's.) Then they came up with the formulation of "creation science," picking up on anomalies and gaps in evolution and on differences between scientific Darwinists like Richard Dawkins and Stephen Jay Gould. Next came the ingratiating plea for "equal time"—what could be more American than that?—and now we have the rebranded new coinage of "intelligent design" and the fresh complaint that its brave advocates are, so goes the title of a recent self-pitying documentary, simply "expelled" from the discourse.

It's not just that the overwhelming majority of scientists are now convinced that evolution is inscribed in the fossil record and in the lineaments of molecular biology. It is more that evolutionists will say in advance which evidence, if found, would refute them and force them to reconsider. ("Rabbit fossils in the pre-Cambrian layer" was, I seem to remember, the response of Prof. J.B.S. Haldane.) Try asking an "intelligent design" advocate to stipulate upfront what would constitute refutation of his world view and you will easily see the difference between the scientific method and the pseudoscientific one.

But that is just my opinion. And I certainly do not want it said that my side denies a hearing to the opposing one. In the spirit of compromise, then, I propose the following. First, let the school debating societies restage the wonderful set-piece real-life dramas of Oxford and Dayton, Tenn. Let time also be set aside, in our increasingly multiethnic and multicultural school system, for children to be taught the huge variety of creation stories, from the Hindu to the Muslim to the Australian Aboriginal. This is always interesting (and it can't be, can it, that the Texas board holdouts think that only Genesis ought to be so honored?). Second, we can surely demand that the principle of "strengths and weaknesses" will be applied evenly. If any church in Texas receives a tax exemption, or if any religious institution is the beneficiary of any subvention from the Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships, we must be assured that it will devote a portion of its time to laying bare the "strengths and weaknesses" of the religious world view, and also to teaching the works of Voltaire, David Hume, Benedict de Spinoza, Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson. This is America. Let a hundred flowers bloom, and a thousand schools of thought contend. We may one day have cause to be grateful to the Texas Board of Education for lighting a candle that cannot be put out.

Hitchens, a NEWSWEEK contributor, is a columnist for Vanity Fair. His book “God Is Not Great” is newly available in paperback.

http://www.newsweek.com/id/191400/output/print

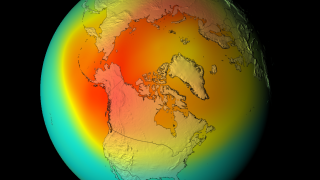

Ozone disaster averted

Led by NASA Goddard scientist Paul Newman, a team of atmospheric chemists simulated 'what might have been' if chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and similar ozone-depleting chemicals were not banned through the Montreal Protocol. The comprehensive model -- including atmospheric chemical effects, wind changes, and solar radiation changes -- simulated what would happen to global concentrations of stratospheric ozone if CFCs were continually added to the atmosphere.

The visualizations below present two cases, from several different viewing positions: the 'world avoided' case, where the rate of CFC emission into the atmosphere is assumed to be that of the period before regulation, and the 'projected' case, which assumes the current rate of emission, post-regulation. Both cases extrapolate to the year 2065.

link

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

Scientists warn of a world on the brink

THE world is on the brink of dangerous climate change and immediate action is needed to avert it, scientists say, issuing one of the bleakest assessments yet of the current state of the planet.

A strongly worded communique marking the end of a specially convened conference in Copenhagen on Thursday, European time, concluded that climate change and its effects matched or exceeded the worst fears expressed by the Nobel prize-winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change two years ago.

The statement, issued on behalf of 2500 scientists from 80 countries, will be passed to world leaders in the coming months. Their summary of what global warming is doing to the planet warned policymakers: "There is no excuse for inaction."

The demands and alerts contained in the statement were described as a defining moment in scientists' relations with political leaders, representing a shift away from their traditional role of merely offering advice to telling politicians to act. Katherine Richardson of the University of Copenhagen, who organised the conference, said: "We need the politicians to realise what a risk they are taking on behalf of their constituents, the world and, even more importantly, future generations.

"All of the signals from the earth system and the climate system show us that we are on a path that will have enormous and unacceptable consequences."

Findings from this week's conference, designed to identify changes in scientific understanding of climate change, will be presented to world leaders and policymakers who will converge on the city in December to try to agree on an international deal to bring greenhouse gas emissions under control. Recent observations of climatic trends, the new statement said, showed that the worst-case trajectories highlighted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2007 were being followed or exceeded on a range of measurements.

"There is a significant risk that many of the trends will accelerate, leading to an increasing risk of abrupt or irreversible climatic shifts," it said.

Scientists called for rapid, sustained and effective mitigation programs to bring down greenhouse gas emissions.

They were particularly concerned that any significant delay in reducing emissions would lead to a range of tipping points being reached that would make it significantly more difficult to reduce greenhouse gas levels.

There was also a warning for politicians negotiating targets designed to reduce emissions. It was an implicit rebuff to Silvio Berlusconi and other European leaders who attempted last year to reduce the EU's commitment to cutting emissions.

The scientists said the tools to beat climate change already existed and if vigorously implemented, they would enable governments to bring about low-carbon economies around the world.

The Times

A strongly worded communique marking the end of a specially convened conference in Copenhagen on Thursday, European time, concluded that climate change and its effects matched or exceeded the worst fears expressed by the Nobel prize-winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change two years ago.

The statement, issued on behalf of 2500 scientists from 80 countries, will be passed to world leaders in the coming months. Their summary of what global warming is doing to the planet warned policymakers: "There is no excuse for inaction."

The demands and alerts contained in the statement were described as a defining moment in scientists' relations with political leaders, representing a shift away from their traditional role of merely offering advice to telling politicians to act. Katherine Richardson of the University of Copenhagen, who organised the conference, said: "We need the politicians to realise what a risk they are taking on behalf of their constituents, the world and, even more importantly, future generations.

"All of the signals from the earth system and the climate system show us that we are on a path that will have enormous and unacceptable consequences."

Findings from this week's conference, designed to identify changes in scientific understanding of climate change, will be presented to world leaders and policymakers who will converge on the city in December to try to agree on an international deal to bring greenhouse gas emissions under control. Recent observations of climatic trends, the new statement said, showed that the worst-case trajectories highlighted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2007 were being followed or exceeded on a range of measurements.

"There is a significant risk that many of the trends will accelerate, leading to an increasing risk of abrupt or irreversible climatic shifts," it said.

Scientists called for rapid, sustained and effective mitigation programs to bring down greenhouse gas emissions.

They were particularly concerned that any significant delay in reducing emissions would lead to a range of tipping points being reached that would make it significantly more difficult to reduce greenhouse gas levels.

There was also a warning for politicians negotiating targets designed to reduce emissions. It was an implicit rebuff to Silvio Berlusconi and other European leaders who attempted last year to reduce the EU's commitment to cutting emissions.

The scientists said the tools to beat climate change already existed and if vigorously implemented, they would enable governments to bring about low-carbon economies around the world.

The Times

Sunday, March 15, 2009

Google library a windfall for authors

March 14, 2009

Australian authors and publishers are set to receive a windfall from

Google's project to put millions of books online.

In recent weeks several Australian publishing industry bodies, such

as the Australian Society of Authors, the Copyright Agency Limited

and the Australian Publishers' Association, have been contacting

members to let them know about the settlement Google has reached with

American authors and publishers.

Under the terms of this settlement, copyright holders are to be paid

$US60 ($91.85) a book and $US15 an article or chapter copied from the

more than 7 million items in the Google Library project.

The project, accessible online only in the US, will allow internet

users to download and search any book scanned from the collections of

11 major American university libraries. When the book generates

income, either from direct use or from advertising, Google will pay

the copyright holder 63 per cent of that income on top of the initial

opt-in fee.

Google had tried to ignore the copyright owners but American authors

and publishers started a class action against it. The parties settled

the matter last year. The chief executive of the copyright agency,

Jim Alexander, hailed the agreement as "a substantial victory for

copyright owners".

Authors and publishers have been notified that they may either opt in

or out of the deal by May 5. If they opt out, Google may not use

their book in any way. If they opt in, the copyright holders are

entitled to a share in revenues and fees.

"What this does is put the copyright owner back in control," Mr

Alexander said. He said it was impossible to estimate how many

Australian authors and publishers among the agency's 13,000 members

would benefit. Google has assigned $US125 million to compensate

copyright holders and set up a book rights registry that will

independently oversee how payments are allocated.

A Google spokesman, Rob Shilkin, said Google Australia had been

waiting for the US deal to be bedded down, but once it was, the

company would approach potential Australian partners with a view to

undertaking a similar project.

Malcolm Knox is a director of the Copyright Agency Limited.

Australian authors and publishers are set to receive a windfall from

Google's project to put millions of books online.

In recent weeks several Australian publishing industry bodies, such

as the Australian Society of Authors, the Copyright Agency Limited

and the Australian Publishers' Association, have been contacting

members to let them know about the settlement Google has reached with

American authors and publishers.

Under the terms of this settlement, copyright holders are to be paid

$US60 ($91.85) a book and $US15 an article or chapter copied from the

more than 7 million items in the Google Library project.

The project, accessible online only in the US, will allow internet

users to download and search any book scanned from the collections of

11 major American university libraries. When the book generates

income, either from direct use or from advertising, Google will pay

the copyright holder 63 per cent of that income on top of the initial

opt-in fee.

Google had tried to ignore the copyright owners but American authors

and publishers started a class action against it. The parties settled

the matter last year. The chief executive of the copyright agency,

Jim Alexander, hailed the agreement as "a substantial victory for

copyright owners".

Authors and publishers have been notified that they may either opt in

or out of the deal by May 5. If they opt out, Google may not use

their book in any way. If they opt in, the copyright holders are

entitled to a share in revenues and fees.

"What this does is put the copyright owner back in control," Mr

Alexander said. He said it was impossible to estimate how many

Australian authors and publishers among the agency's 13,000 members

would benefit. Google has assigned $US125 million to compensate

copyright holders and set up a book rights registry that will

independently oversee how payments are allocated.

A Google spokesman, Rob Shilkin, said Google Australia had been

waiting for the US deal to be bedded down, but once it was, the

company would approach potential Australian partners with a view to

undertaking a similar project.

Malcolm Knox is a director of the Copyright Agency Limited.

Saturday, March 14, 2009

Let Me Chew My Coca Leaves

Evo Morales

THIS week in Vienna, a meeting of the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs took place that will help shape international antidrug efforts for the next 10 years. I attended the meeting to reaffirm Bolivia’s commitment to this struggle but also to call for the reversal of a mistake made 48 years ago.

In 1961, the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs placed the coca leaf in the same category with cocaine — thus promoting the false notion that the coca leaf is a narcotic — and ordered that “coca leaf chewing must be abolished within 25 years from the coming into force of this convention.” Bolivia signed the convention in 1976, during the brutal dictatorship of Col. Hugo Banzer, and the 25-year deadline expired in 2001.

So for the past eight years, the millions of us who maintain the traditional practice of chewing coca have been, according to the convention, criminals who violate international law. This is an unacceptable and absurd state of affairs for Bolivians and other Andean peoples.

Many plants have small quantities of various chemical compounds called alkaloids. One common alkaloid is caffeine, which is found in more than 50 varieties of plants, from coffee to cacao, and even in the flowers of orange and lemon trees. Excessive use of caffeine can cause nervousness, elevated pulse, insomnia and other unwanted effects.

Another common alkaloid is nicotine, found in the tobacco plant. Its consumption can lead to addiction, high blood pressure and cancer; smoking causes one in five deaths in the United States. Some alkaloids have important medicinal qualities. Quinine, for example, the first known treatment for malaria, was discovered by the Quechua Indians of Peru in the bark of the cinchona tree.

The coca leaf also has alkaloids; the one that concerns antidrug officials is the cocaine alkaloid, which amounts to less than one-tenth of a percent of the leaf. But as the above examples show, that a plant, leaf or flower contains a minimal amount of alkaloids does not make it a narcotic. To be made into a narcotic, alkaloids must typically be extracted, concentrated and in many cases processed chemically. What is absurd about the 1961 convention is that it considers the coca leaf in its natural, unaltered state to be a narcotic. The paste or the concentrate that is extracted from the coca leaf, commonly known as cocaine, is indeed a narcotic, but the plant itself is not.

Why is Bolivia so concerned with the coca leaf? Because it is an important symbol of the history and identity of the indigenous cultures of the Andes.

The custom of chewing coca leaves has existed in the Andean region of South America since at least 3000 B.C. It helps mitigate the sensation of hunger, offers energy during long days of labor and helps counter altitude sickness. Unlike nicotine or caffeine, it causes no harm to human health nor addiction or altered state, and it is effective in the struggle against obesity, a major problem in many modern societies.

Today, millions of people chew coca in Bolivia, Colombia, Peru and northern Argentina and Chile. The coca leaf continues to have ritual, religious and cultural significance that transcends indigenous cultures and encompasses the mestizo population.

Mistakes are an unavoidable part of human history, but sometimes we have the opportunity to correct them. It is time for the international community to reverse its misguided policy toward the coca leaf.

Evo Morales Ayma is the president of Bolivia.

THIS week in Vienna, a meeting of the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs took place that will help shape international antidrug efforts for the next 10 years. I attended the meeting to reaffirm Bolivia’s commitment to this struggle but also to call for the reversal of a mistake made 48 years ago.

In 1961, the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs placed the coca leaf in the same category with cocaine — thus promoting the false notion that the coca leaf is a narcotic — and ordered that “coca leaf chewing must be abolished within 25 years from the coming into force of this convention.” Bolivia signed the convention in 1976, during the brutal dictatorship of Col. Hugo Banzer, and the 25-year deadline expired in 2001.

So for the past eight years, the millions of us who maintain the traditional practice of chewing coca have been, according to the convention, criminals who violate international law. This is an unacceptable and absurd state of affairs for Bolivians and other Andean peoples.

Many plants have small quantities of various chemical compounds called alkaloids. One common alkaloid is caffeine, which is found in more than 50 varieties of plants, from coffee to cacao, and even in the flowers of orange and lemon trees. Excessive use of caffeine can cause nervousness, elevated pulse, insomnia and other unwanted effects.

Another common alkaloid is nicotine, found in the tobacco plant. Its consumption can lead to addiction, high blood pressure and cancer; smoking causes one in five deaths in the United States. Some alkaloids have important medicinal qualities. Quinine, for example, the first known treatment for malaria, was discovered by the Quechua Indians of Peru in the bark of the cinchona tree.

The coca leaf also has alkaloids; the one that concerns antidrug officials is the cocaine alkaloid, which amounts to less than one-tenth of a percent of the leaf. But as the above examples show, that a plant, leaf or flower contains a minimal amount of alkaloids does not make it a narcotic. To be made into a narcotic, alkaloids must typically be extracted, concentrated and in many cases processed chemically. What is absurd about the 1961 convention is that it considers the coca leaf in its natural, unaltered state to be a narcotic. The paste or the concentrate that is extracted from the coca leaf, commonly known as cocaine, is indeed a narcotic, but the plant itself is not.

Why is Bolivia so concerned with the coca leaf? Because it is an important symbol of the history and identity of the indigenous cultures of the Andes.

The custom of chewing coca leaves has existed in the Andean region of South America since at least 3000 B.C. It helps mitigate the sensation of hunger, offers energy during long days of labor and helps counter altitude sickness. Unlike nicotine or caffeine, it causes no harm to human health nor addiction or altered state, and it is effective in the struggle against obesity, a major problem in many modern societies.

Today, millions of people chew coca in Bolivia, Colombia, Peru and northern Argentina and Chile. The coca leaf continues to have ritual, religious and cultural significance that transcends indigenous cultures and encompasses the mestizo population.

Mistakes are an unavoidable part of human history, but sometimes we have the opportunity to correct them. It is time for the international community to reverse its misguided policy toward the coca leaf.

Evo Morales Ayma is the president of Bolivia.

Thursday, March 12, 2009

Why the Sun seems to be 'dimming'

We are all seeing rather less of the Sun, according to scientists who have been looking at five decades of sunlight measurements.

They have reached the disturbing conclusion that the amount of solar energy reaching the Earth's surface has been gradually falling.

Paradoxically, the decline in sunlight may mean that global warming is a far greater threat to society than previously thought.

The effect was first spotted by Gerry Stanhill, an English scientist working in Israel.

Cloud changes

Comparing Israeli sunlight records from the 1950s with current ones, Dr Stanhill was astonished to find a large fall in solar radiation.

"There was a staggering 22% drop in the sunlight, and that really amazed me." Intrigued, he searched records from all around the world, and found the same story almost everywhere he looked.

Sunlight was falling by 10% over the USA, nearly 30% in parts of the former Soviet Union, and even by 16% in parts of the British Isles.

Although the effect varied greatly from place to place, overall the decline amounted to one to two per cent globally every decade between the 1950s and the 1990s.

Dr Stanhill called it "global dimming", but his research, published in 2001, met a sceptical response from other scientists.

It was only recently, when his conclusions were confirmed by Australian scientists using a completely different method to estimate solar radiation, that climate scientists at last woke up to the reality of global dimming.

My main concern is global dimming is also having a detrimental impact on the Asian monsoon ... We are talking about billions of people

Professor Veerhabhadran Ramanathan

Dimming appears to be caused by air pollution.

Burning coal, oil and wood, whether in cars, power stations or cooking fires, produces not only invisible carbon dioxide - the principal greenhouse gas responsible for global warming - but also tiny airborne particles of soot, ash, sulphur compounds and other pollutants.

This visible air pollution reflects sunlight back into space, preventing it reaching the surface. But the pollution also changes the optical properties of clouds.

Because the particles seed the formation of water droplets, polluted clouds contain a larger number of droplets than unpolluted clouds.

Recent research shows that this makes them more reflective than they would otherwise be, again reflecting the Sun's rays back into space.

Scientists are now worried that dimming, by shielding the oceans from the full power of the Sun, may be disrupting the pattern of the world's rainfall.

There are suggestions that dimming was behind the droughts in sub-Saharan Africa which claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in the 1970s and 80s.

There are disturbing hints the same thing may be happening today in Asia, home to half the world's population.

"My main concern is global dimming is also having a detrimental impact on the Asian monsoon," says Professor Veerhabhadran Ramanathan, professor of climate and atmospheric sciences at the University of California, San Diego. "We are talking about billions of people."

Alarming energy

But perhaps the most alarming aspect of global dimming is that it may have led scientists to underestimate the true power of the greenhouse effect.

They know how much extra energy is being trapped in the Earth's atmosphere by the extra carbon dioxide we have placed there.

What has been surprising is that this extra energy has so far resulted in a temperature rise of just 0.6 degree Celsius.

This has led many scientists to conclude that the present-day climate is less sensitive to the effects of carbon dioxide than it was, say, during the ice age, when a similar rise in CO2 led to a temperature rise of six degrees Celsius.

But it now appears the warming from greenhouse gases has been offset by a strong cooling effect from dimming - in effect two of our pollutants have been cancelling each other out.

This means that the climate may in fact be more sensitive to the greenhouse effect than previously thought.

If so, then this is bad news, according to Dr Peter Cox, one of the world's leading climate modellers.

As things stand, CO2 levels are projected to rise strongly over coming decades, whereas there are encouraging signs that particle pollution is at last being brought under control.

"We're going to be in a situation unless we act where the cooling pollutant is dropping off while the warming pollutant is going up.

"That means we'll get reducing cooling and increased heating at the same time and that's a problem for us," says Dr Cox.

Even the most pessimistic forecasts of global warming may now have to be drastically revised upwards.

That means a temperature rise of 10 degrees Celsius by 2100 could be on the cards, giving the UK a climate like that of North Africa, and rendering many parts of the world uninhabitable.

That is unless we act urgently to curb our emissions of greenhouse gases.

You can see more on this report on Thursday's Horizon, BBC Two, at 9.00pm GMT.

link

They have reached the disturbing conclusion that the amount of solar energy reaching the Earth's surface has been gradually falling.

Paradoxically, the decline in sunlight may mean that global warming is a far greater threat to society than previously thought.

The effect was first spotted by Gerry Stanhill, an English scientist working in Israel.

Cloud changes

Comparing Israeli sunlight records from the 1950s with current ones, Dr Stanhill was astonished to find a large fall in solar radiation.

"There was a staggering 22% drop in the sunlight, and that really amazed me." Intrigued, he searched records from all around the world, and found the same story almost everywhere he looked.

Sunlight was falling by 10% over the USA, nearly 30% in parts of the former Soviet Union, and even by 16% in parts of the British Isles.

Although the effect varied greatly from place to place, overall the decline amounted to one to two per cent globally every decade between the 1950s and the 1990s.

Dr Stanhill called it "global dimming", but his research, published in 2001, met a sceptical response from other scientists.

It was only recently, when his conclusions were confirmed by Australian scientists using a completely different method to estimate solar radiation, that climate scientists at last woke up to the reality of global dimming.

My main concern is global dimming is also having a detrimental impact on the Asian monsoon ... We are talking about billions of people

Professor Veerhabhadran Ramanathan

Dimming appears to be caused by air pollution.

Burning coal, oil and wood, whether in cars, power stations or cooking fires, produces not only invisible carbon dioxide - the principal greenhouse gas responsible for global warming - but also tiny airborne particles of soot, ash, sulphur compounds and other pollutants.

This visible air pollution reflects sunlight back into space, preventing it reaching the surface. But the pollution also changes the optical properties of clouds.

Because the particles seed the formation of water droplets, polluted clouds contain a larger number of droplets than unpolluted clouds.

Recent research shows that this makes them more reflective than they would otherwise be, again reflecting the Sun's rays back into space.

Scientists are now worried that dimming, by shielding the oceans from the full power of the Sun, may be disrupting the pattern of the world's rainfall.

There are suggestions that dimming was behind the droughts in sub-Saharan Africa which claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in the 1970s and 80s.

There are disturbing hints the same thing may be happening today in Asia, home to half the world's population.

"My main concern is global dimming is also having a detrimental impact on the Asian monsoon," says Professor Veerhabhadran Ramanathan, professor of climate and atmospheric sciences at the University of California, San Diego. "We are talking about billions of people."

Alarming energy

But perhaps the most alarming aspect of global dimming is that it may have led scientists to underestimate the true power of the greenhouse effect.

They know how much extra energy is being trapped in the Earth's atmosphere by the extra carbon dioxide we have placed there.

What has been surprising is that this extra energy has so far resulted in a temperature rise of just 0.6 degree Celsius.

This has led many scientists to conclude that the present-day climate is less sensitive to the effects of carbon dioxide than it was, say, during the ice age, when a similar rise in CO2 led to a temperature rise of six degrees Celsius.

But it now appears the warming from greenhouse gases has been offset by a strong cooling effect from dimming - in effect two of our pollutants have been cancelling each other out.

This means that the climate may in fact be more sensitive to the greenhouse effect than previously thought.

If so, then this is bad news, according to Dr Peter Cox, one of the world's leading climate modellers.

As things stand, CO2 levels are projected to rise strongly over coming decades, whereas there are encouraging signs that particle pollution is at last being brought under control.

"We're going to be in a situation unless we act where the cooling pollutant is dropping off while the warming pollutant is going up.

"That means we'll get reducing cooling and increased heating at the same time and that's a problem for us," says Dr Cox.

Even the most pessimistic forecasts of global warming may now have to be drastically revised upwards.

That means a temperature rise of 10 degrees Celsius by 2100 could be on the cards, giving the UK a climate like that of North Africa, and rendering many parts of the world uninhabitable.

That is unless we act urgently to curb our emissions of greenhouse gases.

You can see more on this report on Thursday's Horizon, BBC Two, at 9.00pm GMT.

link

Sunday, March 1, 2009

Greenland, Antarctica Glaciers Speeding Faster Toward the Sea

Feb. 26 (Bloomberg) -- Glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica are melting faster than predicted, accelerating their march to the sea and adding to the rising ocean levels that threaten coastal communities worldwide.

The Pine Island Glacier, the biggest in West Antarctica, has sped 40 percent faster toward the sea since the 1970s and Smith Glacier is moving 83 percent quicker than 15 years ago, said David Hik, executive director of the Canadian secretariat of the International Polar Year, an international scientific project.

“The loss of ice is pretty spectacular,” Hik, a professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, said today in a telephone interview from Geneva. “The big outflow glaciers on Greenland are accelerating their discharge as well.”

The study means scientists now have a better handle on the potential contribution to sea-level rise of melting ice sheets than two years ago, when the United Nations produced its biggest report on global warming, predicting an increase in sea levels of 18 to 59 centimeters (7 to 23 inches) this century.

The UN acknowledged a lack of certainty about ice loss from Antarctica. The latest findings will help refine climate-change modeling and predictions of future sea-level rise, Hik said.

“Altogether, the glaciers in the West Antarctic are losing about 103 billion tons a year of ice in discharge,” he said. “This discharge from west Antarctica would add an additional 10 to 20 centimeters” to the existing UN predictions of sea level rise this century, he said.

While the UN said a complete melt of the West Antarctic ice sheet is unlikely this century, Hik said “we thought lots of things were unlikely even two years ago.” A collapse of the sheet could add 1 to 1.5 meters to sea levels this century, he said.

“The effects of warming are going to be global,” Hik said. “What happens at the poles will influence all parts of the planet and it’s very evident that we can see rapid changes in sea level associated with changes in the Arctic and Antarctic.”

International Polar Year drew in 50,000 researchers from 63 countries, according to Hik. The project spanned two years, ending next month, to incorporate a full year each of the Arctic in the north and the Antarctic in the south.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Morales in London at amorales2@bloomberg.net.

Last Updated: February 26, 2009 10:35 EST

The Pine Island Glacier, the biggest in West Antarctica, has sped 40 percent faster toward the sea since the 1970s and Smith Glacier is moving 83 percent quicker than 15 years ago, said David Hik, executive director of the Canadian secretariat of the International Polar Year, an international scientific project.

“The loss of ice is pretty spectacular,” Hik, a professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, said today in a telephone interview from Geneva. “The big outflow glaciers on Greenland are accelerating their discharge as well.”

The study means scientists now have a better handle on the potential contribution to sea-level rise of melting ice sheets than two years ago, when the United Nations produced its biggest report on global warming, predicting an increase in sea levels of 18 to 59 centimeters (7 to 23 inches) this century.

The UN acknowledged a lack of certainty about ice loss from Antarctica. The latest findings will help refine climate-change modeling and predictions of future sea-level rise, Hik said.

“Altogether, the glaciers in the West Antarctic are losing about 103 billion tons a year of ice in discharge,” he said. “This discharge from west Antarctica would add an additional 10 to 20 centimeters” to the existing UN predictions of sea level rise this century, he said.

While the UN said a complete melt of the West Antarctic ice sheet is unlikely this century, Hik said “we thought lots of things were unlikely even two years ago.” A collapse of the sheet could add 1 to 1.5 meters to sea levels this century, he said.

“The effects of warming are going to be global,” Hik said. “What happens at the poles will influence all parts of the planet and it’s very evident that we can see rapid changes in sea level associated with changes in the Arctic and Antarctic.”

International Polar Year drew in 50,000 researchers from 63 countries, according to Hik. The project spanned two years, ending next month, to incorporate a full year each of the Arctic in the north and the Antarctic in the south.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alex Morales in London at amorales2@bloomberg.net.

Last Updated: February 26, 2009 10:35 EST

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)