We don't innovate with energy because it is too cheap...but we will all be innovating big time sooner or later......not starving in the dark.

“Leibig’s Law” states that growth in a system is controlled not by the total of resources available, but by the scarcest resource (limiting factor). How does this apply energy production? I have about 7.20E+03 pounds of lead in my home PV system. Global production of lead is about 3.88E+06 tonnes per year. The 1.30E+08 homes in the US would require 9.36E+11 pounds (4.25E+08 tonnes) of lead every eight or so years. For alternate energy storage in homes, the US alone would need 100 times the current global production of lead – six times the global reserves of lead – just for US home electrical storage (that number DOES NOT include transportation or business)! Therefore, we know that it’s literally impossible for alternative energy to replace fossil fuels. It’s literally true that “peak oil” is equivalent to “peak everything.” More on scarce minerals at http://www.theoildrum.com/node/5559 http://europe.theoildrum.com/node/5239

I send your post to my engineering friend, Here are his comments:

This guy is living the standard brainless clueless USA energy hog existence with 7000 lb. worth of batteries. In contrast Barbara Kerr (Kerr-Cole Sustainable Living Center) gets by on 480 lb. and I live happily with 240 lb. of batteries. Nonetheless he has the right idea regarding lead. According to globalleadnet.com STRONG>/ STRONG> /FONT> STRONG>/ STRONG> /file_download/17/5.pdf the US production was from 477,000 metric tonnes of 65% ore concentrate, which works out to 680,000,000 lb. in primary lead (not from recycling) sources (mining) in 1991. This is enough to supply 1000 lb of batteries to 680,000 new installations. Presumably existing installations will recycle lead, and therefore will neither add nor subtract from the lead supply. This guy forgot that lead is not consumed in batteries in 8 years; it is nearly 100% recyclable. He forgets that there are other battery technologies that will come into the mix: nickel-metal-hydride (my Prius for example) and lithium ion (the coming plug-in Prius for example). The future probably lies in running your house partially off the car battery using grid-tie EV technology - and learning to live with severe electrical energy rationing (by today's standards). This guy is also ignorant of compressed air automotive technology. And of power grid storage options such as hydrogen, ammonia (a much more practical offshoot of hydrogen), compressed air, flywheels and pumped hydro for on-demand electricity production. Not everybody needs batteries in a renewable, alternative technology. One can use the grid via net metering to store what one generates, or just buy the alternative juice from the utility.

Most important, he is neglecting geothermal energy which is a base load technology (runs 24/7 and therefore does not require any storage whatsoever). I am right now at one of the most advanced geothermal plants in the world, Chena Hot Springs near Fairbanks. The maverick entrepreneur owner of this spa put in a cutting edge power plant a three years ago on his own nickel (well 2.5 megabucks, actually) for 1/5 the cost of conventional technology, mainly by modifying a standard industrial chiller to operate in reverse using mostly off-the shelf components (with concomitant economies of scale using reliable mature design equipment that has been in production for decades). He has cut his electrical energy cost by $500,000 dollars a year because he has replaced diesel ($0.50 per kWh operating cost) with geo ($0.02 per kWh operating cost). The key innovation is that it runs off low relatively low temperature hot water, making it operable from deep earth heated water from depleted oil wells. This the "geothermal anywhere" (GA) concept. He is now going into the business of putting 200 kW mobile power plants on a semi trailers and leasing them out to wherever waste heat or easy geothermal is available. The first two mobile units are supplying power to this community and my computer right now as they undergo pre-delivery testing (they are temporarily replacing the on-site power plant). Very soon they will take a 6000 mile trip to Florida to run on oil well waste heat.

The installed plant here produces twice the power the community needs (for emergency backup redundancy for service down-time or failure of one of the generators). So he just put in a hydrogen electrolysis plant to transport "stranded" excess energy capacity to market. Waste heat warms four-season greenhouses (the tomato plants are 14 months old and producing like gangbusters). He has all the lighting he wants to keep the grow lights on in the winter 24/7, 100 miles from the arctic circle. He plans to become self-sufficient in food.

Interesting, huh? You might think about relocating to a community with hot spring or depleted oil well. There may be a future in it.

Monday, August 31, 2009

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

Holding heavy objects makes us see things as more important

Its like Taleb says, we only think we are thinking and our judgement is very weak, it can only be strong if we always remain aware of just how weak it is...

Gravity affects not just our bodies and our behaviours, but our very thoughts. That's the fascinating conclusion of a new study which shows that simply holding a heavy object can affect the way we think. A simple heavy clipboard can makes issues seem weightier - when holding one, volunteers think of situations as more important and they invest more mental effort in dealing with abstract issues.

In a variety of languages, from English to Dutch to Chinese, importance is often described by words pertaining to weight. We speak of 'heavy news, 'weighty matters' and 'light entertainment'. We weigh up the value of evidence, we lend weight to arguments with facts, and our opinions carry weight if we wield influence and authority. These are more than just quirks of language - they reflect real links that our minds make between weight and importance.

Nils Jostmann from the University of Amsterdam demonstrated the link between weight and importance through a quartet of experiments. In each one, a different set of volunteers held a clipboard that either weighed 1.5 pounds or 2.3 pounds.

The extra 0.8 pounds were enough to make volunteers think that a foreign currency was worth more money. Forty volunteers were asked to guess the conversion rates between euros and six other currencies, indicating their estimate by marking a straight line. Those who held the heavier clipboard valued the currencies more generously, even though a separate questionnaire showed that they felt the same about the euro.

Money, of course, does have its own weight, so for his next trick, Jostmann wanted to stay entirely within the abstract realm. He considered justice - an area that is free of weight but hardly free of importance. Jostmann showed 50 volunteers a scenario where a university committee was denying students the opportunity to voice their opinions on a study grant. It was a potentially weighty issue, but more so to the students who held the heavy clipboard. They felt it was more important that the university listened to the students' opinions.

Jostmann also showed that people are less likely to take matters lightly if they're holding something heavier. In his third task, he asked 49 recruits to rate the mayor of Amsterdam in terms of his competence, likeability, powerlessness, trustworthiness, intelligence, corruption, importance and charisma. They also had to give their opinion about Amsterdam itself - whether it was a great city and how much they enjoyed being in it. The weight of the clipboards didn't affect the evaluations of either the mayor or the city. However, the two sets of scores were more strongly correlated among the volunteers who held the heavier board.

Jostmann thinks that the extra weight made people invest that little bit more mental effort in awarding their scores - hence the more consistent rankings across the mayor- and city-based questions. This result, I feel, is a bit more tenuous. Jostmann argues the case that satisfaction with the mayor is an indirect measure of satisfaction with the city, so the two scores should match to some extent. That seems reasonable, but it hasn't been demonstrated, which makes interpreting the study a bit more difficult.

In the final task, 40 visitors were asked to say whether they agreed with six statements about the construction of a controversial new subway that was big news at the time. The list included three arguments that previous volunteers had deemed as weak (e.g. the building of the subway is a sign of courage to handle large-scale projects) and three arguments that were stronger (e.g. the subway will make the city more accessible).

In all cases, the volunteers agreed more with the strong arguments but especially so if they held the heavier clipboards. This group were also more confident in their opinions and were more likely to be clearly in favour of the subway or against it, rather than dawdling on the fence. Again, the results suggest that under the influence of the weightier board, people make stronger and more polarised judgments, and they do so more confidently.

The effects of the clipboards were small but statistically significant - unlikely to have arisen by chance. The boards didn't affect the moods of the volunteers, and with a weight of just 2.3 pounds, no one felt that the heavier board was actually burdensome to hold.

Instead, Jostmann reasons that the link between weight and importance is rooted in our early childhood experiences, when we rapidly learn that heavy objects require more effort to deal with, not just in terms of strength but planning too. Our brain relies on these concrete physical experiences when it represents more abstract concepts, like importance. The two are then joined, so that physical experiences can affect abstract thought.

This is far from the first study that has supported this "theory of embodied cognition". Jostmann's explanation can also account for why thinking clean thoughts can soften moral judgments and why immoral thoughts trigger a need for physical cleanliness. It's why warming our hands can make us socially warmer, why social exclusion literally feels cold.

Update: Just realised that I've been totally scooped by Vaughan at Mind Hacks. Go over there for another take.

An aside: I love academia. The paper says, "Being hit by a heavy object generally has more profound consequences than being hit by a light object." I will remember this the next time I'm hit by a heavy object. Instead of a primal scream, I will opt for a more dignified, "Lo. I am struck. The consequences are most profound."

Reference: Jostmann, N., Lakens, D., & Schubert, T. (2009). Weight as an Embodiment of Importance Psychological Science DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02426.x

http://scienceblogs.com/notrocketscience/2009/08/holding_heavy_objects_makes_us_see_things_as_more_important.php?utm_source=nytwidget

Gravity affects not just our bodies and our behaviours, but our very thoughts. That's the fascinating conclusion of a new study which shows that simply holding a heavy object can affect the way we think. A simple heavy clipboard can makes issues seem weightier - when holding one, volunteers think of situations as more important and they invest more mental effort in dealing with abstract issues.

In a variety of languages, from English to Dutch to Chinese, importance is often described by words pertaining to weight. We speak of 'heavy news, 'weighty matters' and 'light entertainment'. We weigh up the value of evidence, we lend weight to arguments with facts, and our opinions carry weight if we wield influence and authority. These are more than just quirks of language - they reflect real links that our minds make between weight and importance.

Nils Jostmann from the University of Amsterdam demonstrated the link between weight and importance through a quartet of experiments. In each one, a different set of volunteers held a clipboard that either weighed 1.5 pounds or 2.3 pounds.

The extra 0.8 pounds were enough to make volunteers think that a foreign currency was worth more money. Forty volunteers were asked to guess the conversion rates between euros and six other currencies, indicating their estimate by marking a straight line. Those who held the heavier clipboard valued the currencies more generously, even though a separate questionnaire showed that they felt the same about the euro.

Money, of course, does have its own weight, so for his next trick, Jostmann wanted to stay entirely within the abstract realm. He considered justice - an area that is free of weight but hardly free of importance. Jostmann showed 50 volunteers a scenario where a university committee was denying students the opportunity to voice their opinions on a study grant. It was a potentially weighty issue, but more so to the students who held the heavy clipboard. They felt it was more important that the university listened to the students' opinions.

Jostmann also showed that people are less likely to take matters lightly if they're holding something heavier. In his third task, he asked 49 recruits to rate the mayor of Amsterdam in terms of his competence, likeability, powerlessness, trustworthiness, intelligence, corruption, importance and charisma. They also had to give their opinion about Amsterdam itself - whether it was a great city and how much they enjoyed being in it. The weight of the clipboards didn't affect the evaluations of either the mayor or the city. However, the two sets of scores were more strongly correlated among the volunteers who held the heavier board.

Jostmann thinks that the extra weight made people invest that little bit more mental effort in awarding their scores - hence the more consistent rankings across the mayor- and city-based questions. This result, I feel, is a bit more tenuous. Jostmann argues the case that satisfaction with the mayor is an indirect measure of satisfaction with the city, so the two scores should match to some extent. That seems reasonable, but it hasn't been demonstrated, which makes interpreting the study a bit more difficult.

In the final task, 40 visitors were asked to say whether they agreed with six statements about the construction of a controversial new subway that was big news at the time. The list included three arguments that previous volunteers had deemed as weak (e.g. the building of the subway is a sign of courage to handle large-scale projects) and three arguments that were stronger (e.g. the subway will make the city more accessible).

In all cases, the volunteers agreed more with the strong arguments but especially so if they held the heavier clipboards. This group were also more confident in their opinions and were more likely to be clearly in favour of the subway or against it, rather than dawdling on the fence. Again, the results suggest that under the influence of the weightier board, people make stronger and more polarised judgments, and they do so more confidently.

The effects of the clipboards were small but statistically significant - unlikely to have arisen by chance. The boards didn't affect the moods of the volunteers, and with a weight of just 2.3 pounds, no one felt that the heavier board was actually burdensome to hold.

Instead, Jostmann reasons that the link between weight and importance is rooted in our early childhood experiences, when we rapidly learn that heavy objects require more effort to deal with, not just in terms of strength but planning too. Our brain relies on these concrete physical experiences when it represents more abstract concepts, like importance. The two are then joined, so that physical experiences can affect abstract thought.

This is far from the first study that has supported this "theory of embodied cognition". Jostmann's explanation can also account for why thinking clean thoughts can soften moral judgments and why immoral thoughts trigger a need for physical cleanliness. It's why warming our hands can make us socially warmer, why social exclusion literally feels cold.

Update: Just realised that I've been totally scooped by Vaughan at Mind Hacks. Go over there for another take.

An aside: I love academia. The paper says, "Being hit by a heavy object generally has more profound consequences than being hit by a light object." I will remember this the next time I'm hit by a heavy object. Instead of a primal scream, I will opt for a more dignified, "Lo. I am struck. The consequences are most profound."

Reference: Jostmann, N., Lakens, D., & Schubert, T. (2009). Weight as an Embodiment of Importance Psychological Science DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02426.x

http://scienceblogs.com/notrocketscience/2009/08/holding_heavy_objects_makes_us_see_things_as_more_important.php?utm_source=nytwidget

Sunday, August 23, 2009

Mexico Legalizes Drug Possession

MEXICO CITY (AP) — Mexico enacted a controversial law on Thursday decriminalizing possession of small amounts of marijuana, cocaine, heroin and other drugs while encouraging government-financed treatment for drug dependency free of charge.

The law sets out maximum “personal use” amounts for drugs, also including LSD and methamphetamine. People detained with those quantities will no longer face criminal prosecution; the law goes into effect on Friday.

Anyone caught with drug amounts under the personal-use limit will be encouraged to seek treatment, and for those caught a third time treatment is mandatory — although no penalties for noncompliance are specified.

Mexican authorities said the change only recognized the longstanding practice here of not prosecuting people caught with small amounts of drugs.

The maximum amount of marijuana considered to be for “personal use” under the new law is 5 grams — the equivalent of about four marijuana cigarettes. Other limits are half a gram of cocaine, 50 milligrams of heroin, 40 milligrams for methamphetamine and 0.015 milligrams of LSD.

President Felipe Calderón waited months before approving the law.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/21/world/americas/21mexico.html

The law sets out maximum “personal use” amounts for drugs, also including LSD and methamphetamine. People detained with those quantities will no longer face criminal prosecution; the law goes into effect on Friday.

Anyone caught with drug amounts under the personal-use limit will be encouraged to seek treatment, and for those caught a third time treatment is mandatory — although no penalties for noncompliance are specified.

Mexican authorities said the change only recognized the longstanding practice here of not prosecuting people caught with small amounts of drugs.

The maximum amount of marijuana considered to be for “personal use” under the new law is 5 grams — the equivalent of about four marijuana cigarettes. Other limits are half a gram of cocaine, 50 milligrams of heroin, 40 milligrams for methamphetamine and 0.015 milligrams of LSD.

President Felipe Calderón waited months before approving the law.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/21/world/americas/21mexico.html

Friday, August 21, 2009

Addiction to stimulants may be undiagnosed ADD

I've thought so for awhile, also.

The definitions of addiction have changed over the years, according to Barry Everitt, Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Cambridge. He and his colleagues have done research into addiction, identifying the kind of person who is more likely than others to become addicted to substances, and they have looked at new ways to help people overcome their addictions.

Health Report Audio

The definitions of addiction have changed over the years, according to Barry Everitt, Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Cambridge. He and his colleagues have done research into addiction, identifying the kind of person who is more likely than others to become addicted to substances, and they have looked at new ways to help people overcome their addictions.

Health Report Audio

Thursday, August 13, 2009

a theory of consciousness and a brain the size of a planet

A "Complex" Theory of Consciousness

Is complexity the secret to sentience, to a panpsychic view of consciousness?

By Christof Koch

Do you think that your newest acquisition, a Roomba robotic vacuum cleaner that traces out its unpredictable paths on your living room floor, is conscious? What about that bee that hovers above your marmalade-covered breakfast toast? Or the newborn who finally fell asleep after being suckled? Nobody except a dyed-in-the-wool nerd would think of the first as being sentient; adherents of Jainism, India’s oldest religion, believe that bees—and indeed all living creatures, small and large—are aware; whereas most everyone would accord the magical gift of consciousness to the baby.

The truth is that we really do not know which of these organisms is or is not conscious. We have strong feelings about the matter, molded by tradition, religion and law. But we have no objective, rational method, no step-by-step procedure, to determine whether a given organism has subjective states, has feelings.

The reason is that we lack a coherent framework for consciousness. Although consciousness is the only way we know about the world within and around us—shades of the famous Cartesian deduction cogito, ergo sum—there is no agreement about what it is, how it relates to highly organized matter or what its role in life is. This situation is scandalous! We have a detailed and very successful framework for matter and for energy but not for the mind-body problem. This dismal state of affairs might be about to change, however.

The universal lingua franca of our age is information. We are used to the idea that stock and bond prices, books, photographs, movies, music and our genetic makeup can all be turned into data streams of zeros and ones. These bits are the elemental atoms of information that are transmitted over an Ethernet cable or via wireless, that are stored, replayed, copied and assembled into gigantic repositories of knowledge. Information does not depend on the substrate. The same information can be represented as lines on paper, as electrical charges inside a PC’s memory banks or as the strength of the synaptic connections among nerve cells.

Since the early days of computers, scholars have argued that the subjective, phenomenal states that make up the life of the mind are intimately linked to the information expressed at that time by the brain. Yet they have lacked the tools to turn this hunch into a concrete and predictive theory. Enter psychiatrist and neuroscientist Giulio Tononi of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Tononi has developed and refined what he calls the integrated information theory (IIT) of consciousness.

An Integrated Theory

IIT is based on two axiomatic pillars.

First, conscious states are highly differentiated; they are informationally very rich. You can be conscious of an uncountable number of things: you can watch your son’s piano recital, for instance; you can see the flowers in the garden outside or the Gauguin painting on the wall. Think of all the frames from all the movies you have ever seen or that have ever been filmed or that will be filmed! Each frame, each view, is a specific conscious percept.

Second, this information is highly integrated. No matter how hard you try, you cannot force yourself to see the world in black-and-white, nor can you see only the left half of your field of view and not the right. When you’re looking at your friend’s face, you can’t fail to also notice if she is crying. Whatever information you are conscious of is wholly and completely presented to your mind; it cannot be subdivided. Underlying this unity of consciousness is a multitude of causal interactions among the relevant parts of your brain. If areas of the brain start to disconnect or become fragmented and balkanized, as occurs in deep sleep or in anesthesia, consciousness fades and might cease altogether. Consider split-brain patients, whose corpus callosum—the 200 million wires linking the two cortical hemispheres—has been cut to alleviate severe epileptic seizures. The surgery literally splits the person’s consciousness in two, with one conscious mind associated with the left hemisphere and seeing the right half of the visual field and the other mind arising from the right hemisphere and seeing the left half of the visual field.

To be conscious, then, you need to be a single, integrated entity with a large repertoire of highly differentiated states. Although the 60-gigabyte hard disk on my MacBook exceeds in capacity my lifetime of memories, that information is not integrated. For example, the family photographs on my Macintosh are not linked to one another. The computer does not know that the girl in those pictures is my daughter as she matures from a toddler to a lanky teenager and then a graceful adult. To my Mac, all information is equally meaningless, just a vast, random tapestry of zeros and ones.

Yet I derive meaning from these images because my memories are heavily cross-linked. And the more interconnected, the more meaningful they become. Indeed, Tononi’s IIT postulates that the amount of integrated information that an entity possesses corresponds to its level of consciousness.

These ideas can be precisely expressed in the language of mathematics using notions from information theory such as entropy [see box on next page]. Given a particular brain, with its neurons and axons, dendrites and synapses, one can, in principle, accurately compute the extent to which this brain is integrated. From this calculation, the theory derives a single number, Φ (pronounced “fi”). Measured in bits, Φ denotes the size of the conscious repertoire associated with any network of causally interacting parts. Think of Φ as the synergy of the system. The more integrated the system is, the more synergy it has, the more conscious it is. If individual brain regions are too isolated from one another or are interconnected at random, Φ will be low. If the organism has many neurons and is richly endowed with specific connections, Φ will be high—capturing the quantity of consciousness but not the quality of any one conscious experience. (That value is generated by the informational geometry that is associated with Φ but won’t be discussed here.)

Explaining Brain Facts

The theory can account for a number of puzzling observations. The cerebellum, the “little brain” at the back of the brain that contains more neurons than the convoluted cerebral cortex that crowns the organ, has a regular, crystallinelike wiring arrangement. Thus, its circuit complexity as measured by Φ is low as compared with that of the cerebral cortex. Indeed, if you lose your cerebellum you will never be a rock climber, pianist or ballet dancer, but your consciousness will not be impaired. The cortex and its gateway, the thalamus—the quail egg–shaped structure in the center of the brain—on the other hand, are essential for consciousness, providing it with its elaborate content. Its circuitry conjoins functional specialization with functional integration thanks to extensive reciprocal connections linking distinct cortical regions and the cortex with the thalamus. This corticothalamic complex is well suited to behave as a single dynamic entity endowed with a large number of discriminable states. Lose one chunk of a particular cortical area, and you might be unable to perceive motion. If a different area were lesioned, you would be blind to faces (yet could see the eyes, hair, mouth and ears).

When people are woken from deep sleep, they typically recall experiencing nothing or, at best, only some vague bodily feeling; this experience contrasts with the highly emotional narratives our brains weave during rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep. What is paradoxical is that the average firing activity of individual nerve cells does not differ that much in deep sleep and quiet wakefulness. At the whole system level, though, electroencephalographic electrodes on the skull pick up slow, large and highly synchronized waves during deep sleep. Because these waves are quite regular, they will disrupt the transfer of specific information among brain cells.

Every day, in tens of thousands of surgical operations, patients’ consciousness is quickly, safely and transiently turned off and on again with the help of various anesthetic agents. There is no single mechanism common to all. The most consistent regional finding is that anesthetics reduce thalamic activity and deactivate mesial (middle) and parietal cortical regions. Twenty years of electrical recording in anesthetized laboratory animals provided ample evidence that many cortical cells, particularly in primary sensory cortical regions, continue to respond selectively during anesthesia. What appears to be disrupted is large-scale functional integration in the corticothalamic complex.

IIT explains why consciousness requires neither sensory input nor behavioral output, as happens every night during REM sleep, in which a central paralysis prevents the sleeper from acting out her dreams. All that matters for consciousness is the functional relation among the nerve cells that make up the corticothalamic complex. Within this integrated dynamic entity can be found the dream of the lotus eater, the mindfulness of the meditating monk, the agony of the cancer patient and the Arcadian visions of your lost childhood home. Paraphrasing Oscar Wilde, I would say it is the causal interactions within the dynamic core that make the poppy red, the apple odorous and the skylark sing.

Consciousness Is Universal

One unavoidable consequence of IIT is that all systems that are sufficiently integrated and differentiated will have some minimal consciousness associated with them: not only our beloved dogs and cats but also mice, squid, bees and worms.

Indeed, the theory is blind to synapses and to all-or-none pulses of nervous systems. At least in principle, the incredibly complex molecular interactions within a single cell have nonzero Φ. In the limit, a single hydrogen ion, a proton made up of three quarks, will have a tiny amount of synergy, of Φ. In this sense, IIT is a scientific version of panpsychism, the ancient and widespread belief that all matter, all things, animate or not, are conscious to some extent. Of course, IIT does not downplay the vast gulf that separates the Φ of the common roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans with its 302 nerve cells and the Φ associated with the 20 billion cortical neurons in a human brain.

The theory does not discriminate between squishy brains inside skulls and silicon circuits encased in titanium. Provided that the causal relations among the transistors and memory elements are complex enough, computers or the billions of personal computers on the Internet will have nonzero Φ. The size of Φ could even end up being a yardstick for the intelligence of a machine.

Future Challenges

IIT is in its infancy and lacks the graces of a fully developed theory. A major question that it so far leaves unanswered is, Why should natural selection evolve creatures with high Φ? What benefit for the survival of the organism flows from consciousness? One answer that I hope for is that intelligence, the ability to assess situations never previously encountered and to rapidly come to an appropriate response, requires integrated information. Another possible answer, though, could be that high-Φ circuits do not have any special status in terms of their survival. Just as electrical charge is a fundamental feature of the universe without a function, consciousness might also lack any specific evolutionary role. It just is.

A second stumbling block with IIT is that Φ is exceedingly difficult to compute even for very small systems. To accurately evaluate Φ for the roundworm is utterly unfeasible, even if using all of Google’s more than 100,000 computers. Can we find other algorithms to more easily compute Φ?

A third issue to understand is why so much brain processing and so many of our daily behaviors are unconscious. Do the neural networks that mediate these unconscious, zombielike behaviors have lower Φ than the ones that give rise to consciousness?

Tononi’s integrated information theory of consciousness could be completely wrong. But it challenges us to think deeply about the mind-body problem in a novel, rigorous, and mathematically and empirically minded manner. And that is a great boon to this endeavor.

If Tononi’s equation for Φ proves to plumb the hitherto ineffable—consciousness itself—it would validate the ancient Pythagorean belief that “number is the ruler of forms and ideas and the cause of gods and demons.”

Note: This article was originally printed with the title, "A Theory of Consciousness."

And from that brainy girl, Zoe.......

http://aebrain.blogspot.com/2009/08/artificial-brains-within-10-years.html

As I've blogged about before, there are two approaches to AI - analytic and synthetic.

Here's some news on the progress made in the Analytic approach, where instead of trying to "grow" and AI, we analyse what happens at the cellular level of existing intelligences, and try building a brain out of simulated cells. From RedOrbit :

A leading scientist has claimed that a detailed, functional artificial human brain could be built within the next 10 years, BBC News reported.

Henry Markram, director of the Blue Brain Project, has already simulated elements of a rat brain.

A synthetic human brain would be of particular use finding treatments for mental illnesses, Markram told the TED Global conference in Oxford.

He said some two billion people are thought to suffer some kind of brain impairment and that it is not impossible to build a human brain within 10 years time.

Launched in 2005, the Blue Brain project aims to reverse engineer the mammalian brain from laboratory data, particularly focusing on the neocortical column – the repetitive units of the mammalian brain known as the neocortex.

...

He likened it to cataloguing a bit of the rainforest, as in how may trees does it have, what shape are the trees, how many of each type of tree do we have, what is the position of the trees.

"But it is a bit more than cataloguing because you have to describe and discover all the rules of communication, the rules of connectivity," he added.

His team has been able to digitally construct an artificial neocortical column with a software model of "tens of thousands" of neurons - each one of which is different.

They have found that the patterns of circuitry in different brains have common patterns even though each neuron is unique.

Markram said we do actually share the same fabric even though each brain may be smaller, bigger, or may have different morphologies of neurons.

"And we think this is species specific, which could explain why we can't communicate across species.

The team feeds the models and a few algorithms into a supercomputer to make the model come alive and Markram said since you need one laptop to do all the calculations for one neuron, they would need ten thousand laptops.

But instead they use an IBM Blue Gene machine with 10,000 processors and the simulations have started to give the researchers clues about how the brain works.

For example, they can show the brain a picture of a flower and then follow the electrical activity in the machine, where it creates its own representation.

He said the ultimate goal is to extract that representation and project it so that researchers could see directly how a brain perceives the world.

One thing - the Human brain cas about 100 Billion neurons. However, today's average desktops can simulate maybe a dozen each.

I don't know whether to be amazed at how complex the human brain is, or how simple. Because we'll soon have 10 Billion people on the planet. And if each one had an average desktop of the time, each communication with the 20 or so in the local area... yes, there would exist a network capable of modelling at a fine-scale a human brain. With about the same reaction times too.

A Brain the size of a planet.

I wonder...

Is complexity the secret to sentience, to a panpsychic view of consciousness?

By Christof Koch

Do you think that your newest acquisition, a Roomba robotic vacuum cleaner that traces out its unpredictable paths on your living room floor, is conscious? What about that bee that hovers above your marmalade-covered breakfast toast? Or the newborn who finally fell asleep after being suckled? Nobody except a dyed-in-the-wool nerd would think of the first as being sentient; adherents of Jainism, India’s oldest religion, believe that bees—and indeed all living creatures, small and large—are aware; whereas most everyone would accord the magical gift of consciousness to the baby.

The truth is that we really do not know which of these organisms is or is not conscious. We have strong feelings about the matter, molded by tradition, religion and law. But we have no objective, rational method, no step-by-step procedure, to determine whether a given organism has subjective states, has feelings.

The reason is that we lack a coherent framework for consciousness. Although consciousness is the only way we know about the world within and around us—shades of the famous Cartesian deduction cogito, ergo sum—there is no agreement about what it is, how it relates to highly organized matter or what its role in life is. This situation is scandalous! We have a detailed and very successful framework for matter and for energy but not for the mind-body problem. This dismal state of affairs might be about to change, however.

The universal lingua franca of our age is information. We are used to the idea that stock and bond prices, books, photographs, movies, music and our genetic makeup can all be turned into data streams of zeros and ones. These bits are the elemental atoms of information that are transmitted over an Ethernet cable or via wireless, that are stored, replayed, copied and assembled into gigantic repositories of knowledge. Information does not depend on the substrate. The same information can be represented as lines on paper, as electrical charges inside a PC’s memory banks or as the strength of the synaptic connections among nerve cells.

Since the early days of computers, scholars have argued that the subjective, phenomenal states that make up the life of the mind are intimately linked to the information expressed at that time by the brain. Yet they have lacked the tools to turn this hunch into a concrete and predictive theory. Enter psychiatrist and neuroscientist Giulio Tononi of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Tononi has developed and refined what he calls the integrated information theory (IIT) of consciousness.

An Integrated Theory

IIT is based on two axiomatic pillars.

First, conscious states are highly differentiated; they are informationally very rich. You can be conscious of an uncountable number of things: you can watch your son’s piano recital, for instance; you can see the flowers in the garden outside or the Gauguin painting on the wall. Think of all the frames from all the movies you have ever seen or that have ever been filmed or that will be filmed! Each frame, each view, is a specific conscious percept.

Second, this information is highly integrated. No matter how hard you try, you cannot force yourself to see the world in black-and-white, nor can you see only the left half of your field of view and not the right. When you’re looking at your friend’s face, you can’t fail to also notice if she is crying. Whatever information you are conscious of is wholly and completely presented to your mind; it cannot be subdivided. Underlying this unity of consciousness is a multitude of causal interactions among the relevant parts of your brain. If areas of the brain start to disconnect or become fragmented and balkanized, as occurs in deep sleep or in anesthesia, consciousness fades and might cease altogether. Consider split-brain patients, whose corpus callosum—the 200 million wires linking the two cortical hemispheres—has been cut to alleviate severe epileptic seizures. The surgery literally splits the person’s consciousness in two, with one conscious mind associated with the left hemisphere and seeing the right half of the visual field and the other mind arising from the right hemisphere and seeing the left half of the visual field.

To be conscious, then, you need to be a single, integrated entity with a large repertoire of highly differentiated states. Although the 60-gigabyte hard disk on my MacBook exceeds in capacity my lifetime of memories, that information is not integrated. For example, the family photographs on my Macintosh are not linked to one another. The computer does not know that the girl in those pictures is my daughter as she matures from a toddler to a lanky teenager and then a graceful adult. To my Mac, all information is equally meaningless, just a vast, random tapestry of zeros and ones.

Yet I derive meaning from these images because my memories are heavily cross-linked. And the more interconnected, the more meaningful they become. Indeed, Tononi’s IIT postulates that the amount of integrated information that an entity possesses corresponds to its level of consciousness.

These ideas can be precisely expressed in the language of mathematics using notions from information theory such as entropy [see box on next page]. Given a particular brain, with its neurons and axons, dendrites and synapses, one can, in principle, accurately compute the extent to which this brain is integrated. From this calculation, the theory derives a single number, Φ (pronounced “fi”). Measured in bits, Φ denotes the size of the conscious repertoire associated with any network of causally interacting parts. Think of Φ as the synergy of the system. The more integrated the system is, the more synergy it has, the more conscious it is. If individual brain regions are too isolated from one another or are interconnected at random, Φ will be low. If the organism has many neurons and is richly endowed with specific connections, Φ will be high—capturing the quantity of consciousness but not the quality of any one conscious experience. (That value is generated by the informational geometry that is associated with Φ but won’t be discussed here.)

Explaining Brain Facts

The theory can account for a number of puzzling observations. The cerebellum, the “little brain” at the back of the brain that contains more neurons than the convoluted cerebral cortex that crowns the organ, has a regular, crystallinelike wiring arrangement. Thus, its circuit complexity as measured by Φ is low as compared with that of the cerebral cortex. Indeed, if you lose your cerebellum you will never be a rock climber, pianist or ballet dancer, but your consciousness will not be impaired. The cortex and its gateway, the thalamus—the quail egg–shaped structure in the center of the brain—on the other hand, are essential for consciousness, providing it with its elaborate content. Its circuitry conjoins functional specialization with functional integration thanks to extensive reciprocal connections linking distinct cortical regions and the cortex with the thalamus. This corticothalamic complex is well suited to behave as a single dynamic entity endowed with a large number of discriminable states. Lose one chunk of a particular cortical area, and you might be unable to perceive motion. If a different area were lesioned, you would be blind to faces (yet could see the eyes, hair, mouth and ears).

When people are woken from deep sleep, they typically recall experiencing nothing or, at best, only some vague bodily feeling; this experience contrasts with the highly emotional narratives our brains weave during rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep. What is paradoxical is that the average firing activity of individual nerve cells does not differ that much in deep sleep and quiet wakefulness. At the whole system level, though, electroencephalographic electrodes on the skull pick up slow, large and highly synchronized waves during deep sleep. Because these waves are quite regular, they will disrupt the transfer of specific information among brain cells.

Every day, in tens of thousands of surgical operations, patients’ consciousness is quickly, safely and transiently turned off and on again with the help of various anesthetic agents. There is no single mechanism common to all. The most consistent regional finding is that anesthetics reduce thalamic activity and deactivate mesial (middle) and parietal cortical regions. Twenty years of electrical recording in anesthetized laboratory animals provided ample evidence that many cortical cells, particularly in primary sensory cortical regions, continue to respond selectively during anesthesia. What appears to be disrupted is large-scale functional integration in the corticothalamic complex.

IIT explains why consciousness requires neither sensory input nor behavioral output, as happens every night during REM sleep, in which a central paralysis prevents the sleeper from acting out her dreams. All that matters for consciousness is the functional relation among the nerve cells that make up the corticothalamic complex. Within this integrated dynamic entity can be found the dream of the lotus eater, the mindfulness of the meditating monk, the agony of the cancer patient and the Arcadian visions of your lost childhood home. Paraphrasing Oscar Wilde, I would say it is the causal interactions within the dynamic core that make the poppy red, the apple odorous and the skylark sing.

Consciousness Is Universal

One unavoidable consequence of IIT is that all systems that are sufficiently integrated and differentiated will have some minimal consciousness associated with them: not only our beloved dogs and cats but also mice, squid, bees and worms.

Indeed, the theory is blind to synapses and to all-or-none pulses of nervous systems. At least in principle, the incredibly complex molecular interactions within a single cell have nonzero Φ. In the limit, a single hydrogen ion, a proton made up of three quarks, will have a tiny amount of synergy, of Φ. In this sense, IIT is a scientific version of panpsychism, the ancient and widespread belief that all matter, all things, animate or not, are conscious to some extent. Of course, IIT does not downplay the vast gulf that separates the Φ of the common roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans with its 302 nerve cells and the Φ associated with the 20 billion cortical neurons in a human brain.

The theory does not discriminate between squishy brains inside skulls and silicon circuits encased in titanium. Provided that the causal relations among the transistors and memory elements are complex enough, computers or the billions of personal computers on the Internet will have nonzero Φ. The size of Φ could even end up being a yardstick for the intelligence of a machine.

Future Challenges

IIT is in its infancy and lacks the graces of a fully developed theory. A major question that it so far leaves unanswered is, Why should natural selection evolve creatures with high Φ? What benefit for the survival of the organism flows from consciousness? One answer that I hope for is that intelligence, the ability to assess situations never previously encountered and to rapidly come to an appropriate response, requires integrated information. Another possible answer, though, could be that high-Φ circuits do not have any special status in terms of their survival. Just as electrical charge is a fundamental feature of the universe without a function, consciousness might also lack any specific evolutionary role. It just is.

A second stumbling block with IIT is that Φ is exceedingly difficult to compute even for very small systems. To accurately evaluate Φ for the roundworm is utterly unfeasible, even if using all of Google’s more than 100,000 computers. Can we find other algorithms to more easily compute Φ?

A third issue to understand is why so much brain processing and so many of our daily behaviors are unconscious. Do the neural networks that mediate these unconscious, zombielike behaviors have lower Φ than the ones that give rise to consciousness?

Tononi’s integrated information theory of consciousness could be completely wrong. But it challenges us to think deeply about the mind-body problem in a novel, rigorous, and mathematically and empirically minded manner. And that is a great boon to this endeavor.

If Tononi’s equation for Φ proves to plumb the hitherto ineffable—consciousness itself—it would validate the ancient Pythagorean belief that “number is the ruler of forms and ideas and the cause of gods and demons.”

Note: This article was originally printed with the title, "A Theory of Consciousness."

And from that brainy girl, Zoe.......

http://aebrain.blogspot.com/2009/08/artificial-brains-within-10-years.html

As I've blogged about before, there are two approaches to AI - analytic and synthetic.

Here's some news on the progress made in the Analytic approach, where instead of trying to "grow" and AI, we analyse what happens at the cellular level of existing intelligences, and try building a brain out of simulated cells. From RedOrbit :

A leading scientist has claimed that a detailed, functional artificial human brain could be built within the next 10 years, BBC News reported.

Henry Markram, director of the Blue Brain Project, has already simulated elements of a rat brain.

A synthetic human brain would be of particular use finding treatments for mental illnesses, Markram told the TED Global conference in Oxford.

He said some two billion people are thought to suffer some kind of brain impairment and that it is not impossible to build a human brain within 10 years time.

Launched in 2005, the Blue Brain project aims to reverse engineer the mammalian brain from laboratory data, particularly focusing on the neocortical column – the repetitive units of the mammalian brain known as the neocortex.

...

He likened it to cataloguing a bit of the rainforest, as in how may trees does it have, what shape are the trees, how many of each type of tree do we have, what is the position of the trees.

"But it is a bit more than cataloguing because you have to describe and discover all the rules of communication, the rules of connectivity," he added.

His team has been able to digitally construct an artificial neocortical column with a software model of "tens of thousands" of neurons - each one of which is different.

They have found that the patterns of circuitry in different brains have common patterns even though each neuron is unique.

Markram said we do actually share the same fabric even though each brain may be smaller, bigger, or may have different morphologies of neurons.

"And we think this is species specific, which could explain why we can't communicate across species.

The team feeds the models and a few algorithms into a supercomputer to make the model come alive and Markram said since you need one laptop to do all the calculations for one neuron, they would need ten thousand laptops.

But instead they use an IBM Blue Gene machine with 10,000 processors and the simulations have started to give the researchers clues about how the brain works.

For example, they can show the brain a picture of a flower and then follow the electrical activity in the machine, where it creates its own representation.

He said the ultimate goal is to extract that representation and project it so that researchers could see directly how a brain perceives the world.

One thing - the Human brain cas about 100 Billion neurons. However, today's average desktops can simulate maybe a dozen each.

I don't know whether to be amazed at how complex the human brain is, or how simple. Because we'll soon have 10 Billion people on the planet. And if each one had an average desktop of the time, each communication with the 20 or so in the local area... yes, there would exist a network capable of modelling at a fine-scale a human brain. With about the same reaction times too.

A Brain the size of a planet.

I wonder...

Antarctic glacier 'thinning fast'

Antarctic glacier 'thinning fast'

By David Shukman

Science and environment correspondent, BBC News

One of the largest glaciers in Antarctica is thinning four times faster than it was ten years ago, according to research seen by the BBC.

A study of satellite measurements of Pine Island glacier in west Antarctica reveals the surface of the ice is now dropping at a rate of up to 16m a year.

Since 1994, the glacier has lowered by as much as 90m, which has serious implications for sea-level rise.

The work by British scientists appears in Geophysical Research Letters.

The team was led by Professor Duncan Wingham of University College London (UCL).

“ We've known that it's been out of balance for some time, but nothing in the natural world is lost at an accelerating exponential rate like this glacier ”

Andrew Shepherd, Leeds University

Calculations based on the rate of melting 15 years ago had suggested the glacier would last for 600 years. But the new data points to a lifespan for the vast ice stream of only another 100 years.

The rate of loss is fastest in the centre of the glacier and the concern is that if the process continues, the glacier may break up and start to affect the ice sheet further inland.

One of the authors, Professor Andrew Shepherd of Leeds University, said that the melting from the centre of the glacier would add about 3cm to global sea level.

"But the ice trapped behind it is about 20-30cm of sea level rise and as soon as we destabilise or remove the middle of the glacier we don't know really know what's going to happen to the ice behind it," he told BBC News.

"This is unprecedented in this area of Antarctica. We've known that it's been out of balance for some time, but nothing in the natural world is lost at an accelerating exponential rate like this glacier."

Pine Island glacier has been the subject of an intense research effort in recent years amid fears that its collapse could lead to a rapid disintegration of the West Antarctic ice sheet.

Five years ago, I joined a flight by the Chilean Navy and Nasa to survey Pine Island glacier with radar and laser equipment.

The 11-hour round-trip from Punta Arenas included a series of low-level passes over the massive ice stream which is 20 miles wide and in places more than one mile thick.

Back then, the researchers on board were concerned at the speed of change they were detecting. This latest study of the satellite data will add to the alarm among polar specialists.

This comes as scientists in the Arctic are finding evidence of dramatic change. Researchers on board a Greenpeace vessel have been studying the northwestern part of Greenland.

One of those taking part, Professor Jason Box of Ohio State University, has been surprised by how little sea ice they encountered in the Nares Strait between Greenland and Canada.

He has also set up time lapse cameras to monitor the massive Petermann glacier. Huge new cracks have been observed and it's expected that a major part of it could break off imminently.

Professor Box told BBC News: "The science community has been surprised by how sensitive these large glaciers are to climate warming. First it was the glaciers in south Greenland and now as we move further north in Greenland we find retreat at major glaciers. It's like removing a cork from a bottle."

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8200680.stm

By David Shukman

Science and environment correspondent, BBC News

One of the largest glaciers in Antarctica is thinning four times faster than it was ten years ago, according to research seen by the BBC.

A study of satellite measurements of Pine Island glacier in west Antarctica reveals the surface of the ice is now dropping at a rate of up to 16m a year.

Since 1994, the glacier has lowered by as much as 90m, which has serious implications for sea-level rise.

The work by British scientists appears in Geophysical Research Letters.

The team was led by Professor Duncan Wingham of University College London (UCL).

“ We've known that it's been out of balance for some time, but nothing in the natural world is lost at an accelerating exponential rate like this glacier ”

Andrew Shepherd, Leeds University

Calculations based on the rate of melting 15 years ago had suggested the glacier would last for 600 years. But the new data points to a lifespan for the vast ice stream of only another 100 years.

The rate of loss is fastest in the centre of the glacier and the concern is that if the process continues, the glacier may break up and start to affect the ice sheet further inland.

One of the authors, Professor Andrew Shepherd of Leeds University, said that the melting from the centre of the glacier would add about 3cm to global sea level.

"But the ice trapped behind it is about 20-30cm of sea level rise and as soon as we destabilise or remove the middle of the glacier we don't know really know what's going to happen to the ice behind it," he told BBC News.

"This is unprecedented in this area of Antarctica. We've known that it's been out of balance for some time, but nothing in the natural world is lost at an accelerating exponential rate like this glacier."

Pine Island glacier has been the subject of an intense research effort in recent years amid fears that its collapse could lead to a rapid disintegration of the West Antarctic ice sheet.

Five years ago, I joined a flight by the Chilean Navy and Nasa to survey Pine Island glacier with radar and laser equipment.

The 11-hour round-trip from Punta Arenas included a series of low-level passes over the massive ice stream which is 20 miles wide and in places more than one mile thick.

Back then, the researchers on board were concerned at the speed of change they were detecting. This latest study of the satellite data will add to the alarm among polar specialists.

This comes as scientists in the Arctic are finding evidence of dramatic change. Researchers on board a Greenpeace vessel have been studying the northwestern part of Greenland.

One of those taking part, Professor Jason Box of Ohio State University, has been surprised by how little sea ice they encountered in the Nares Strait between Greenland and Canada.

He has also set up time lapse cameras to monitor the massive Petermann glacier. Huge new cracks have been observed and it's expected that a major part of it could break off imminently.

Professor Box told BBC News: "The science community has been surprised by how sensitive these large glaciers are to climate warming. First it was the glaciers in south Greenland and now as we move further north in Greenland we find retreat at major glaciers. It's like removing a cork from a bottle."

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8200680.stm

Monday, August 10, 2009

Alternate health strategies work, you got that! ~ in praise of Vitamin D and sugar

Hat tip to Duncan.

NewsTarget.com 10/08/2009 08:00

(NaturalNews) Jerome, a 53-year-old high school teacher, was in the hospital awaiting amputation of his left leg. He'd been receiving IV antibiotics to treat a diabetic ulcer, a wide, oozing open wound on his ankle, but this didn't halt the steady advance of gangrene, and he was told they had no choice but to take his leg.

About five hours before he was scheduled for surgery, Jerome talked to the teacher who was substituting for him to tell him he'd probably be out for the rest of the year. The substitute had heard about the Whitaker Wellness Institute and the work we do here, so he suggested that Jerome check us out. Jerome immediately phoned his wife, who called the clinic and asked if there was anything we could do to save his leg. I said we would certainly try. Figuring he had nothing to lose, Jerome left the hospital-against strongly worded medical advice-and came to my clinic that same day.

"I Wouldn't Be Walking Today" We immediately started Jerome on two therapies. First, he began a course of EDTA chelation, an IV treatment that improves circulation. Second, we dressed his ulcer with sugar. That's right, white table sugar. We simply poured sugar into the wound, wrapped it up, and changed the dressing regularly. Within days he noticed a difference.

"I could see the sores were starting to get better and the swelling had gone down. At first the leg was almost all black. Then it started to get pinkish. It was just amazing how it continued to feel so much better." Within three weeks, Jerome's ulcer was healed, and he was able to resume teaching and coaching the girl's softball team.

"I didn't know anything about alternative medicine when I went to see you. I guess I was skeptical because I had no idea what to expect. I just felt that it was my last hope. I wouldn't be walking today if it weren't for you. I've often thought about sending a card to the doctor who wanted to amputate, with a picture of my leg, and say, 'I still have it.'"

5,000 Years of Success Chelation is an amazing treatment, however, in this article I want to focus on sugar because it is an incredibly powerful therapy that was instrumental in saving Jerome's leg. I've been using sugar to dress open wounds for 20-plus years, but this therapy has been around for much longer-at least 5,000 years.

Honey (which works just like sugar) is mentioned in the world's earliest known medical document, discovered in Luxor, Egypt, in 1862. Known as the Edwin Smith Papyrus, it was written around 1600 BC and is believed to be based on materials from as early as 3000 BC. This ancient manuscript is essentially a textbook on traumatic surgery, and it describes anatomy, examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of a variety of injuries in great detail. In particular, it tells how honey, along with animal fat, herbs, roots, bark, spices, and cat dung, can be used to treat open wounds and burns.

Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician who lived in Rome in the first century AD, also extolled the therapeutic powers of honey. In his five-volume De Materia Medica, which was the primary pharmacopeia in Europe and the Middle East for 16 centuries, he described honey as "good for all rotten and hollow ulcers." In fact, honey-and later, sugar-continued to be widely used to treat wounds well into the twentieth century. Then antibiotics came along.

Better Than Antibiotics Today, antibiotic ointments are the treatment of choice for ulcers, cuts, scrapes, and burns. Yet honey and sugar are far superior to any antibiotic ointment ever used. Antibiotics aren't as effective as they once were, because bacteria rapidly becomes resistant to them. While an antibiotic kills most of the bacteria, the stronger ones-those with some genetic variation that allows them to withstand the effects of the drug-survive and reproduce. Over time, that strain of bacteria becomes completely resistant to the effects of the antibiotic. Another antibiotic comes on the market that kills most of these "superbugs," and the process starts over again.

Today, antibiotic resistance has reached a critical mass: Many infections do not respond to any antibiotics at all. This is what happened to Jerome and the 82,000 other Americans who lose a leg or foot to non-healing diabetic ulcers annually. It's also what affects the two million patients who acquire an infection while they're in the hospital and the 90,000 who die from these infections every year.

Wounds are particularly prone to infection because the gauze used to dress them absorbs fluid from the wound and becomes a breeding ground for bacteria and fungus. Drug companies are working around the clock to come up with antibiotics that stay one step ahead of microbes. Yet, the solution is as near as your sugar bowl. The reason? Bacteria cannot become resistant to the killing effects of sugar or honey.

Sweet, Powerful Medicine When sugar or honey is packed on top of and inside of an open wound, it dissolves in the fluid exuding from the wound, creating a hyperosmotic, or highly concentrated, medium. Bacteria cannot live in a hyperosmotic environment any more than a goldfish could survive in the Great Salt Lake. Scientists have tested the viability of many types of bacteria, including Klebsiella, Shigella, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pyogenes, and none of them have been able to survive in a honey or sugar solution.

In addition to curbing infection, this therapy facilitates healing in other ways. It draws fluid out of the wound, which reduces edema (swelling). It provides a covering or filling and therefore prevents scabbing. It encourages the removal of dead tissue to make way for new growth. It promotes granulation, the formation of connective tissue and blood vessels on the surfaces of a wound. Finally, it supports the growth of new skin covering the wound. The net result is rapid healing with minimal scarring.

This Doctor Has Treated 7,000 Wounds The country's, if not the world's, leading expert on the use of sugar as a wound dressing is Richard A. Knutson, MD, now retired but for many years an orthopedic surgeon at the Delta Medical Center in Greenville, Mississippi. Dr. Knutson first learned about the healing power of sugar from an elderly nurse who worked in the hospital where he was making rounds to check on his patients. When he expressed concern about a patient's bedsore that was so deep it was down to the bone, she told him, "In the old days, we used to put sugar on them wounds."

Although he was dubious, he gave it a try. To his surprise, it worked like a charm. Within a couple of days the wound was free of pus, and with continued use of sugar dressings, healing was complete. Dr. Knutson, a meticulous record keeper, went on to treat and document nearly 7,000 wounds of all sizes and degrees of severity: ulcers, abrasions, lacerations, amputations, abscesses, gunshot wounds, frostbite, punctures, post-operative incisions, cat scratches, burns, and bites (dog, human, snake, spider, and, believe it or not, one lion bite).

He told me about a patient who had accidentally shot himself in the foot at close range with a shotgun. I saw pictures of this, and it was incredible: a perfectly round, inch-and-a-half diameter hole right through his foot. After the bleeding was stopped and the wound cleaned, Dr. Knutson packed it with sugar and wrapped it up. Seven weeks later it had healed completely, and today the patient is fully functional.

Burns: No Skin Grafts, No Scarring Sugar dressings are also great for burns. Most burn centers insist on using silver sulfadiazine, an antibiotic ointment, to treat burns, but it doesn't work nearly as well as sugar or honey.

In a study published in the Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters, 900 patients who presented with second-degree burns were treated with either honey or an antibiotic ointment. All burns were then covered with gauze and bandaged, and the dressing was changed every other day. The 450 patients treated with honey fared much better than those receiving the usual treatment. They healed faster, in an average of nine days compared to 13.5 days in the antibiotic group. They had fewer infections, 5.5 percent versus 12 percent. And minor scarring occurred in only 6.2 percent of the honey-treated patients, while a whopping 20 percent of those receiving conventional treatment ended up with scars.

Dr. Knutson's experience mirrors the results of this study. He has treated 1,622 burns with sugar dressings, and virtually all of them were infection-free and required no antibiotics or skin grafts. He told me about one patient with extensive burns who received antibiotic treatment on some areas of his body and sugar on others. The sugar-treated burns healed faster and scarred less.

If It's So Good, Why Isn't It Used? Trying to figure out why inexpensive, effective therapies like sugar and honey dressings aren't being used is an exercise in futility. That's because there is no rational explanation. Some physicians claim it would cause elevations in blood sugar, which is nonsense because sugar or honey used on an open wound does not enter the bloodstream. Others think it's unscientific or just plain weird.

I suspect it's because, like so many other overlooked therapies, it doesn't fit into the model of conventional medicine. It isn't a drug. It costs pennies. It can be administered by the patient as easily as by a nurse or doctor, so it doesn't require many return office visits. Whatever the reason, do not expect your doctor to offer this therapy or even be open to it. But next time you get a cut, scrape, or burn, give it a try, and let me know how it works.

Protocol for Treating Wounds With Sugar Sugar or honey dressing may be used to treat any kind of open wound or burn. (We use sugar at the clinic because it's less messy.) It will not work on abscesses or pustules that are covered with skin. Do not use on a bleeding wound as sugar promotes bleeding.

1)Unravel a 4" x 4" piece of gauze into a long strip and coat it with Vaseline. Place it around the outside edges of the wound, like a donut. 2)Cover the wound with 1/4-inch of sugar. (The Vaseline "donut" will keep it in place.) 3)Place a 4" x 4" sponge on top of the wound. Bandage it firmly but not too snugly with a cling dressing. 4)Change the dressing every one or two days. Remove, irrigate with water, saline, or hydrogen peroxide, pat dry, and repeat steps 1-3.

Reference Subrahmanyam M. Honey dressing for burns-an appraisal. Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters. 1996;IX:33-35.

About the author

Reprinted from Dr. Julian Whitaker's Health and Healing with permission from Healthy Directions, LLC. For information on subscribing to this newsletter, visit www.drwhitaker.com Dr. Whitaker founded the Whitaker Wellness Institute. Today, it is the largest alternative medicine clinic in the United States. To learn more, visit www.whitakerwellness.com or call (800) 488-1500.

(NaturalNews) Sufficient vitamin D intake may play a critical role in maintaining brain function later in life, according to a study conducted by researchers from the University of Manchester and published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

"This is further evidence from observational studies that vitamin D is likely to be beneficial to reduce many age-related diseases," said Tim Spector of King's College London, who was not involved in the study. "Taken together with similar data that shows its importance in reducing arthritis, osteoporotic fractures, as well as heart disease and some cancers, this underscores the importance of vitamin D for humans and why evolution gave us a liking for the sun."

Researchers measured blood levels of vitamin D in more than 3,000 European men between the ages of 40 and 79 then had the men undergo various tests of mental function, including memory and information processing. They found that the men with the highest blood levels did best on the test, while those with the lowest levels performed worst.

Another study earlier this year also found that higher levels of vitamin D appeared to protect against age-related cognitive decline.

The researchers were not able to determine which biological pathways vitamin D might act through to protect the aging brain, but they hypothesized that it might increase levels of protective antioxidants, increase key hormone levels, or suppress a hyperactive immune system that can lead to brain degeneration.

The researchers warned that vitamin D deficiency is widespread, especially among the elderly, who have decreased absorption from both food and sun sources.

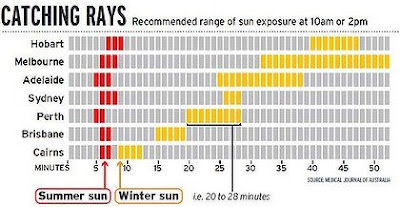

Vitamin D is synthesized by the body when the sun is exposed to the sun's ultraviolet rays. The average light-skinned person can get enough vitamin D from roughly 15 minutes of sun on their face and hands per day, significantly less than the time it takes to burn. Darker skinned people, the elderly, and those living far from the equator (particularly during the winter) may need more sun to synthesize the same amount.

Sources for this story include: news.bbc.co.uk

NewsTarget.com 10/08/2009 08:00

(NaturalNews) Jerome, a 53-year-old high school teacher, was in the hospital awaiting amputation of his left leg. He'd been receiving IV antibiotics to treat a diabetic ulcer, a wide, oozing open wound on his ankle, but this didn't halt the steady advance of gangrene, and he was told they had no choice but to take his leg.

About five hours before he was scheduled for surgery, Jerome talked to the teacher who was substituting for him to tell him he'd probably be out for the rest of the year. The substitute had heard about the Whitaker Wellness Institute and the work we do here, so he suggested that Jerome check us out. Jerome immediately phoned his wife, who called the clinic and asked if there was anything we could do to save his leg. I said we would certainly try. Figuring he had nothing to lose, Jerome left the hospital-against strongly worded medical advice-and came to my clinic that same day.

"I Wouldn't Be Walking Today" We immediately started Jerome on two therapies. First, he began a course of EDTA chelation, an IV treatment that improves circulation. Second, we dressed his ulcer with sugar. That's right, white table sugar. We simply poured sugar into the wound, wrapped it up, and changed the dressing regularly. Within days he noticed a difference.

"I could see the sores were starting to get better and the swelling had gone down. At first the leg was almost all black. Then it started to get pinkish. It was just amazing how it continued to feel so much better." Within three weeks, Jerome's ulcer was healed, and he was able to resume teaching and coaching the girl's softball team.

"I didn't know anything about alternative medicine when I went to see you. I guess I was skeptical because I had no idea what to expect. I just felt that it was my last hope. I wouldn't be walking today if it weren't for you. I've often thought about sending a card to the doctor who wanted to amputate, with a picture of my leg, and say, 'I still have it.'"

5,000 Years of Success Chelation is an amazing treatment, however, in this article I want to focus on sugar because it is an incredibly powerful therapy that was instrumental in saving Jerome's leg. I've been using sugar to dress open wounds for 20-plus years, but this therapy has been around for much longer-at least 5,000 years.

Honey (which works just like sugar) is mentioned in the world's earliest known medical document, discovered in Luxor, Egypt, in 1862. Known as the Edwin Smith Papyrus, it was written around 1600 BC and is believed to be based on materials from as early as 3000 BC. This ancient manuscript is essentially a textbook on traumatic surgery, and it describes anatomy, examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of a variety of injuries in great detail. In particular, it tells how honey, along with animal fat, herbs, roots, bark, spices, and cat dung, can be used to treat open wounds and burns.

Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician who lived in Rome in the first century AD, also extolled the therapeutic powers of honey. In his five-volume De Materia Medica, which was the primary pharmacopeia in Europe and the Middle East for 16 centuries, he described honey as "good for all rotten and hollow ulcers." In fact, honey-and later, sugar-continued to be widely used to treat wounds well into the twentieth century. Then antibiotics came along.

Better Than Antibiotics Today, antibiotic ointments are the treatment of choice for ulcers, cuts, scrapes, and burns. Yet honey and sugar are far superior to any antibiotic ointment ever used. Antibiotics aren't as effective as they once were, because bacteria rapidly becomes resistant to them. While an antibiotic kills most of the bacteria, the stronger ones-those with some genetic variation that allows them to withstand the effects of the drug-survive and reproduce. Over time, that strain of bacteria becomes completely resistant to the effects of the antibiotic. Another antibiotic comes on the market that kills most of these "superbugs," and the process starts over again.

Today, antibiotic resistance has reached a critical mass: Many infections do not respond to any antibiotics at all. This is what happened to Jerome and the 82,000 other Americans who lose a leg or foot to non-healing diabetic ulcers annually. It's also what affects the two million patients who acquire an infection while they're in the hospital and the 90,000 who die from these infections every year.

Wounds are particularly prone to infection because the gauze used to dress them absorbs fluid from the wound and becomes a breeding ground for bacteria and fungus. Drug companies are working around the clock to come up with antibiotics that stay one step ahead of microbes. Yet, the solution is as near as your sugar bowl. The reason? Bacteria cannot become resistant to the killing effects of sugar or honey.

Sweet, Powerful Medicine When sugar or honey is packed on top of and inside of an open wound, it dissolves in the fluid exuding from the wound, creating a hyperosmotic, or highly concentrated, medium. Bacteria cannot live in a hyperosmotic environment any more than a goldfish could survive in the Great Salt Lake. Scientists have tested the viability of many types of bacteria, including Klebsiella, Shigella, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pyogenes, and none of them have been able to survive in a honey or sugar solution.

In addition to curbing infection, this therapy facilitates healing in other ways. It draws fluid out of the wound, which reduces edema (swelling). It provides a covering or filling and therefore prevents scabbing. It encourages the removal of dead tissue to make way for new growth. It promotes granulation, the formation of connective tissue and blood vessels on the surfaces of a wound. Finally, it supports the growth of new skin covering the wound. The net result is rapid healing with minimal scarring.